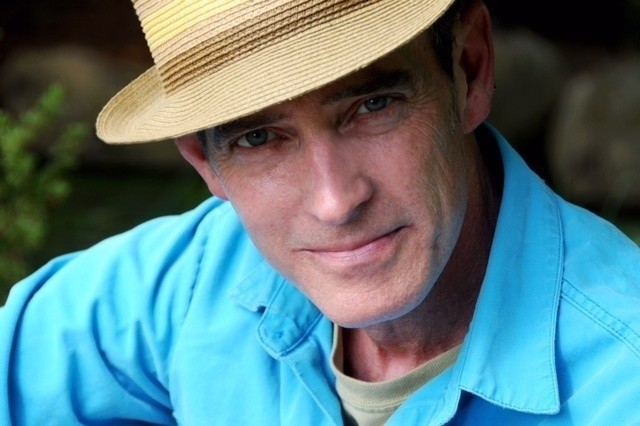

On September 14, 2017, the University of Rhode Island’s music department continued on with its weekly convocation with special guest, Richard Reed. Reed enlightened the crowd with a vibrant and comical, yet utterly honest, recollection of his abrupt hearing loss.

From a young age, music was a defining part of his being. His music career made a debut at the age of 13 with a plethora of gigs and live performances in and around Providence, Rhode Island. Likewise, Reed continued to play throughout high school and college and, following his enrollment to the University of Rhode Island, he decided he just “wanted to go out on the road with a band.” He toured with Blues and R&B bands, but it soon came to a halt as a result of his moderate hearing loss. His hearing loss went from not being able to hear an alarm clock, or the whistling of a tea kettle, to complete silence.

For 10 years, the man who “felt at ease in a crowd,” began avoiding social interaction that would took a toll on his psyche and confidence. Even after receiving an analog hearing aid, the music didn’t sound the way he remembered it. Every sound in his vicinity was amplified, every note, every scale, just sounded like a cacophony.

Despite his lack of hearing, he didn’t give up. He still continued to go to the Newport Blues Café for gigs with his friends, but the mistakes he made, such as playing in the wrong key and jamming on a piano that wasn’t plugged in correctly, lowered his self-confidence and made his bold acts seem less worth it. It wasn’t until his niece Grace came into his life, that he decided to receive cochlear implant surgery.

Grace was around 2 ½ when he made the decision. Every encounter together they would exchange a funny face or sound, without any true language which made interaction easy. However, the older she got, the wider the barrier of communication between the two grew. So, he scheduled the surgery for what was coincidentally her 3rd birthday so he wouldn’t lose their connection.

Perhaps the most comical part of the whole convocation was the description Reed made to the audience of how things sounded following his surgery. After he was implanted, he lost all residual hearing. However, after a month, things started to get better. Reed’s follow-up doctor’s appointment consisted of a dialogue between his doctor and him. Reed notified the audience that her words were inaudible, but the changes in pitch, which he mimicked on his piano, allowed him to assume what the doctor was saying. The doctor’s, “can you hear me,” sounded like bells, but were bells nonetheless. Reed mentioned his astonishment with it all “it felt kind of like she had been inside my brain…she could’ve at least bought me breakfast first.”

Like a cascade, things started falling back into place, he could hear his own footsteps, he could hear the jangle as he dropped his keys on the ground multiple times, it was all of the little things that made him feel whole again, human. It took practice and patience to make sense of songs, something that had once come so naturally to him, but his brain adapted and used musical and motor memories to make sense of it all.

Reed’s first rule of his implants were low expectations, which made his miraculous outcome stand out so much to him. However, he has created a program for other implantees, called “Hope Notes” and does various trials for cochlear implants all over the world, so those who are going through what he did, or who were born hearing impaired, can have high expectations and a future that involves hearing.

Throughout his story, Reed used his keyboard to relay to the audience what sounds were like to him following his hearing aid and even his cochlear implants. Likewise, a presentation sat behind him displaying witty titles for each section of his story, and also provided visuals and scientific facts for those who might not have been as familiar with terminology or processes.

Despite the specificity of his story, those who aren’t musicians or hearing impaired can take a lot away from Reed’s story. Throughout his life, he went through so much trial and error that “mistakes seemed inconsequential [to him].” Reed learned to “embrace [his] inner distortion,” both literally and metaphorically. His incident made everything sound different, and although things would never sound the same again, he eventually welcomed the new sounds and what they had to offer.