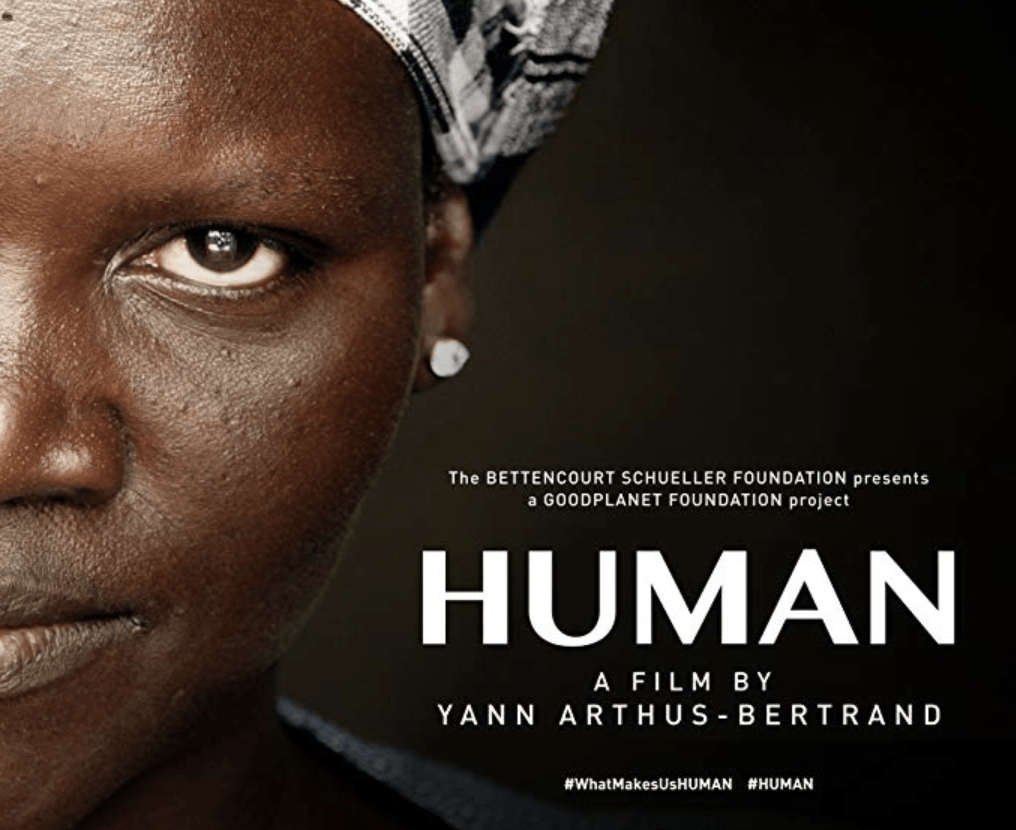

Photo courtesy of IMDb

On Sept. 28th, “Human,” a documentary by filmmaker Yann Arthus-Bertrand was screened in Edwards Auditorium to a crowd of over 100 students, faculty and off-campus visitors. The film, released in 2015, took three years, 2000 interviews from 60 different countries to make, and was first premiered at the General Assembly Hall of the United Nations. However, it was the actual content of the film that was most at the forefront for the entirety of the three-hour screening. Not the behind-the-scenes work that went into the making of it.

Happiness and suffering. War and peace. Family and legacy. Love and violence. According to the film, these are all key components of what makes us human. These aspects of life have been felt and understood by every culture, every society and every civilization since man first painted a bison on their cave walls. It is these concepts that unite us under the human experience, yet they often also serve to drive us apart.

Suffering causes people to withdraw, but it may also drive us back into the arms of those we love. Happiness can make life worth living, yet it can also allow us to take that happiness for granted and in an instant, it can all be gone. Reconciling these ideas, in order to remind ourselves that we are not alone in these feelings unless we make ourselves alone is the underlying concept behind the Yann Arthus-Bertrand’s 2015 film “Human”.

This film doesn’t offer any context. From the starting gun, we are met with a beautiful aerial shot of a group of nomads crossing the desert in a caravan. Which desert, these nomads are in? We do not know. Which ethnic group is on the move? I couldn’t tell you. Why they are risking their lives to traverse such a barren landscape? It’s unclear. The reasoning behind their existence does not matter. Their existence doesn’t need to be justified to anyone. They just exist.

Immediately following this, we hear the story of a man who murdered a woman and a child, yet he feels like his soul has been saved by the love and forgiveness of his victim’s mother, the child’s grandmother. It had no tangible connection to the previous shot, yet it was just another piece in the puzzle of this film. Building to a bigger picture of the totality of the human experience.

The contrast of having grand wide aerial shots of people from the world then close up interviews with strangers giving their answer to the central question is a recurring theme throughout the film.

From the lesbian woman who talked about crying over the thought of going to hell, to the man who talked about being happy that he was allowed two wives, yet his wives were only allowed one husband because he gets jealous, nobody had to justify their existence. Nobody had to argue that they were correct in their beliefs, because at a certain point it doesn’t matter if you are correct. All that matters is that you exist. We all exist. And we are all “Human.”