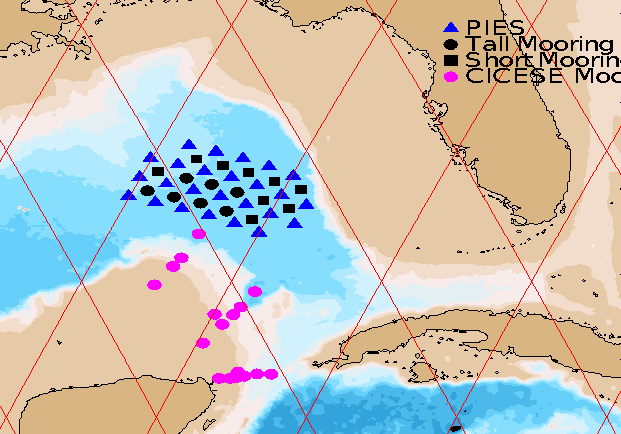

The map above displays where all of the research beacons will be placed in the Gulf in order to study the loop current. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Donahue.

The Oceanography Department at the University of Rhode Island has received a $2 million grant to further study the patterns of the loop current in the Gulf of Mexico.

A total of $10 million was given towards studying the current, which will help fund eight different research projects to better understand and predict the current’s movement.

Kathleen Donahue, a professor of oceanography, said the loop current is a narrow underwater channel with one entrance and exit which carries water and heat from one place to another. Donahue describes it as very similar to the jet stream, which occurs in the atmosphere.

According to Donahue, scientists have already observed that every three to 18 months, the current will swell in size and eventually separate to create an individual pocket of rapidly moving water. This pocket of water is known as a Benthic Storm. One of the main goals of the research will be to predict exactly when this will occur year after year.

Donahue said the motive for funding the research in the first place connects back to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Donahue explained that some of the funding for the research comes from legal settlements over the spill.

“This was a bit of a wakeup call…and [to] put significant funds towards this problem,” Donahue said.

It may seem strange that professors in Rhode Island would be approved to study a natural occurrence a thousand miles away. However, Donahue said she and her colleagues are well prepared to do such research.

“We have expertise with these kinds of experiments,” Donahue said. “My colleagues and I have a long history of working in the Gulf. We have been since 2003.”

Donahue, along with Oceanography Professor Randolph Watts, and five URI alumni will be involved in the research process.

Their first step will take place in June of this year when they will travel to the location of the current and deploy instruments called Current Pressure Inverted Echo Sounders. These will sit on the seafloor 3,000 meters deep and record the bottom movement and pressure of the current.

Then, in October, they will return to the same location and the data will be acoustically transmitted to them, which means they will not have to recover any of the instruments.

This initial campaign is expected to last two years, but 10 years of research is being planned. Donahue described this first project as a jumpstart for additional projects.

Donahue says she is looking forward to learning more about the current while also learning from different perspectives, as one of the URI alumni she will be working with is from Mexico.

“I think we’re going to learn a lot from the data and the collaborations between the groups,” she said.