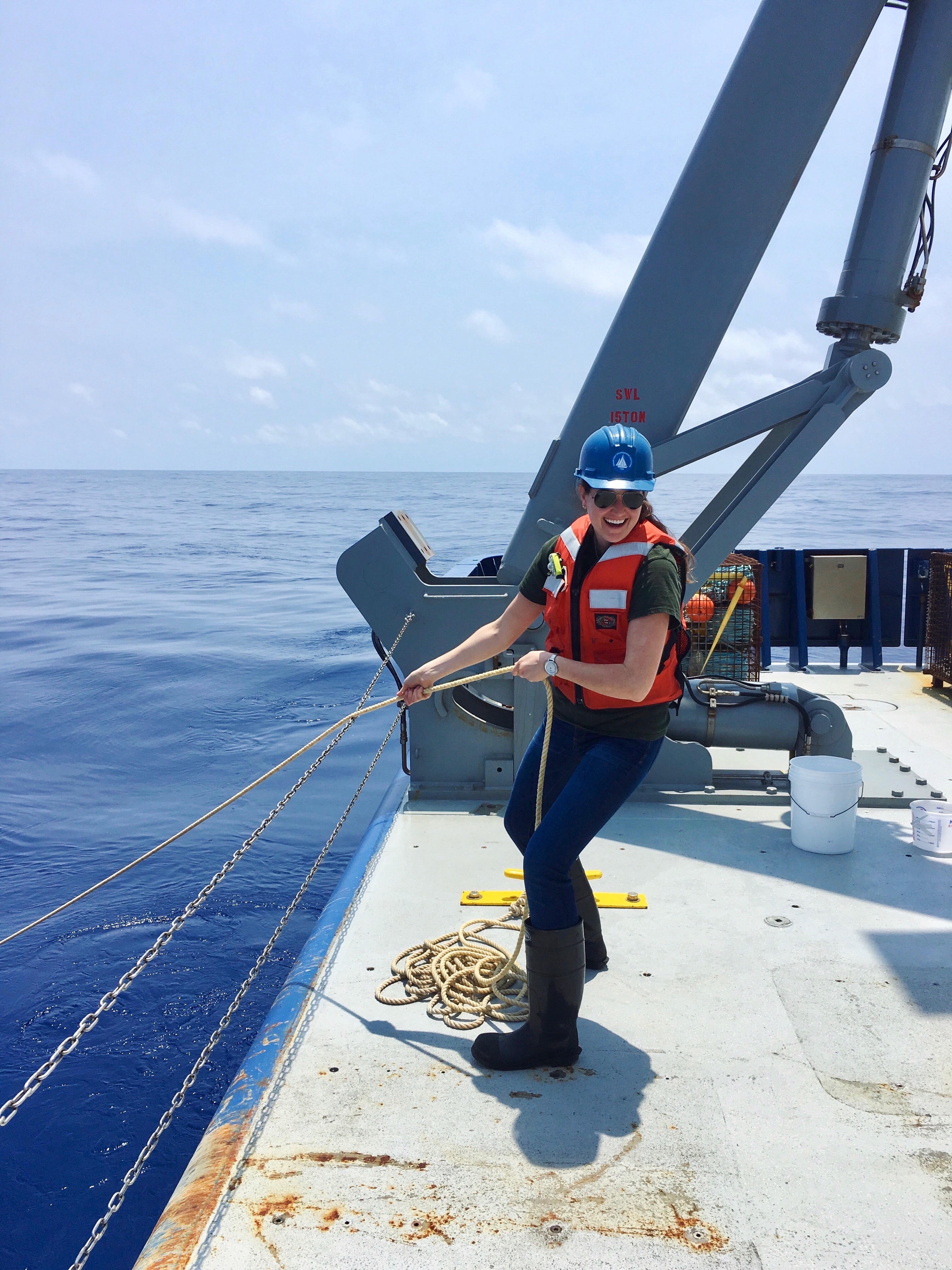

Stephanie Anderson works on a boat, collecting phytoplankton and conducting research to impact the field of science. Photo courtesy of Stephanie Anderson.

Stephanie Anderson, an Oceanography Ph.D. candidate working at the University of Rhode Island Bay Campus, has donated much of her time to volunteer work and is now making an impact on the world of scientific research.

Anderson, 28, is originally from Los Angeles, California, and she has always had an interest in marine life.

“I lived close to the ocean, so it’s always been a big part of my life,” Anderson said. “With the increasing awareness of environmental issues and climate change, I thought it would be really great to focus on the biome that covers 70 percent of the Earth.”

As an undergraduate, Anderson attended the University of Colorado Boulder and majored in cell, molecular and developmental biology.

During her time there, she worked in a lab where she studied a virus that caused cancer by taking proteins from the virus and purifying them. The professor she worked with had helped develop a vaccine to prevent the virus.

“I thought viruses were really cool, but [I] also [knew] vaccine development could have a big impact,” Anderson said.

Anderson also got involved in a teaching assistant program which made her realize she enjoyed teaching. This led her to participate in Teach For America.

Teach For America is a volunteer organization that is a two-year commitment which assigns college students to teach at disadvantaged schools.

With Teach For America, Anderson taught high school-level chemistry to juniors and seniors and science and technology to freshman in central Los Angeles. “It was easily the most difficult thing I’ve ever done, but it’s also probably the time in my life that I grew the most,” Anderson said.

She said that her students were skeptical of her at first since some students in her class were almost her exact age.

“They definitely didn’t trust me, and tested me for a really long time, but I stuck it out, and by the second semester, they were incredible,” Anderson said.

Anderson’s time with Teach For America made her realize that the program is something that anyone interested in education should consider participating in.

“I think it’s also [about] getting to know people from a different background, and hearing their stories, and I think that’s something that everyone should try doing,” she said.

After finishing her two years with Teach For America, Anderson decided it was time to move on because she missed doing research. She soon realized that getting a Ph.D. would provide an opportunity for this.

“I felt like I wasn’t growing in my own science knowledge, so I thought a Ph.D. would be a perfect way to combine both research and science but also the potential to teach later on,” she said.

Today, Anderson works under an advisor at URI’s Narragansett Bay Campus. She studies a kind of phytoplankton found in the Narragansett Bay, known as diatoms. These organisms are covered in a glass-like substance and are very important to the environment, as they are responsible for about 20 percent of oxygen production on Earth.

“Every fifth breath you take is not from a tree,” Anderson explained. “It’s from a plankton in the ocean covered in glass.”

Anderson has been studying how diatoms respond to changes in their environment, specifically with factors like temperature and nutrients. She then tries to determine how this affects the diversity of diatom communities.

Anderson has already made some discoveries regarding this. She and her advisor are writing a research paper that may be available by this summer about the work they did studying the dominant genus of diatom found in Narragansett Bay called Skeletonema.

According to Anderson, it was originally thought that Skeletonema was its own species, but a previous student discovered that there are seven species of Skeletonema in the Bay alone and that some species seemed to occur more often during different seasons than others.

Anderson’s job was to figure out what caused this to happen.

Her first step was to test different species’ physiology in response to temperature, which included measuring growth and elemental composition.

She then took that information and put it into a model to try to recreate their distribution in the Bay using temperature as the only independent variable. The experiment was a success, as she was able to reproduce and therefore predict the timing of the different diatom species down to the week they would occur.

Anderson is currently working on incorporating both nutrients and temperature as variables to look at how both of these factors can alter communities. “Answering one question just makes you ask 20 more,” Anderson said.

She said that while all of these discoveries may not seem to apply to humans, they do connect back in some ways and help explain how the world works.

“Understanding how diversity will change, which species will become dominant, how their entire populations will be positively or negatively affected with climate change, all of this is sort of relevant in terms of both seafood and oxygen production,” Anderson said.