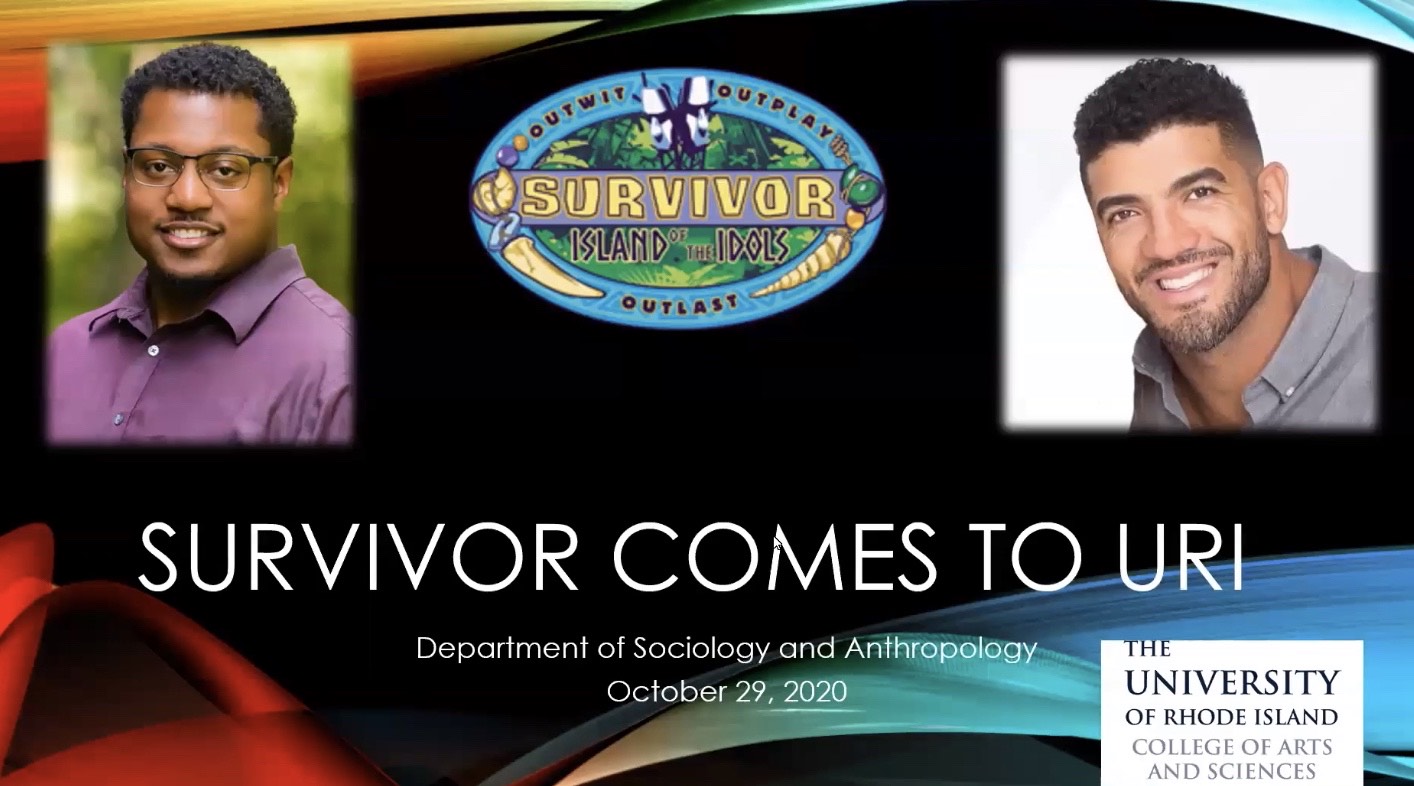

Aaron Meredith and Jamal Shipman, former participants of the show “Survivor,” share their experiences in the competition. Screenshots from Evan McAlice.

Last Thursday, The University of Rhode Island gave a whole new meaning to “the tribe has spoken.”

URI’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology hosted a panel discussion featuring two contestants from the CBS reality show “Survivor” to discuss issues of race and gender that played a prominent role in their season.

The panel featured Aaron Meredith and Jamal Shipman, who both competed on the series’s 39th season, “Island of the Idols.” Meredith is a gym owner from Warwick and Shipman is a consultant for admissions offices from Providence.

Their season of “Survivor” is well known for addressing several social issues that became relevant through events of the show including race, gender, sexual harassment and privilege. The show has been heavily criticized for glossing over similar microaggressions in prior seasons, but it became clear through the editing of “Island of the Idols” that “Survivor”’ was making an effort to change.

“I’m assuming with seasons one to 38, you could’ve easily taken unique situations that mirror issues in society and highlighted them, but ‘Survivor’ chose not to do that,” Meredith said. “With our season, they decided that they were going to use season 39 to show, ‘hey, look, we’re listening. Here you go. You want it? Here it is.’”

One of the season’s controversies occurred when a fellow contestant referred to Shipman’s buff as a durag. As a Black man, this moment made Shipman understand how the game of “Survivor” can still mirror everyday life.

“Anybody who’s of color in the room right now can understand that moment where you’re confronted with the ways that other people perceive you,” Shipman said.

At that moment, Shipman decided to potentially sacrifice his position in the game to have an open discussion about the incident with the other contestant. Shipman credits the strong relationship he built with the other contestant as the reason he was able to have this conversation.

“If that happened day one, I think I would’ve made the decision that we are all confronted with at times,” Shipman said. “Do we set aside our goals for mobility in the game or in life, or do we stand up for ourselves and make a little bit of noise to defend our honor in some way? I don’t know that I would’ve had as open and frank a conversation as I did with him if I didn’t already know that there was a foundation of respect and love and friendship there from the beginning.”

As Black men, Meredith and Shipman both realized the unique hurdles they had to get over in “Survivor” that other white contestants did not. Meredith noted that white contestants with similar body types were seen as far less intimidating than he was. He also had to monitor the conversations he had with fellow Black contestant Missy Byrd out of fear that they would be associated together and subsequently targeted.

Both Meredith and Shipman have been vocal after their stints on the show about how reality television needs to increase the visibility of the issues of people of color. Meredith recalled his experience meeting with CBS executives during the casting process and not seeing any Black people in a room of 30 executives. He stated that change begins with diversity among network executives to make sure people of color are not being portrayed in an overwhelmingly negative or stereotypical light.

“The system of ‘Survivor’ was not designed to incorporate the experiences of different kinds of people,” Shipman said. “People of color’s experiences are really touching, strong issues of what they wrestle with as they’re playing the game.”