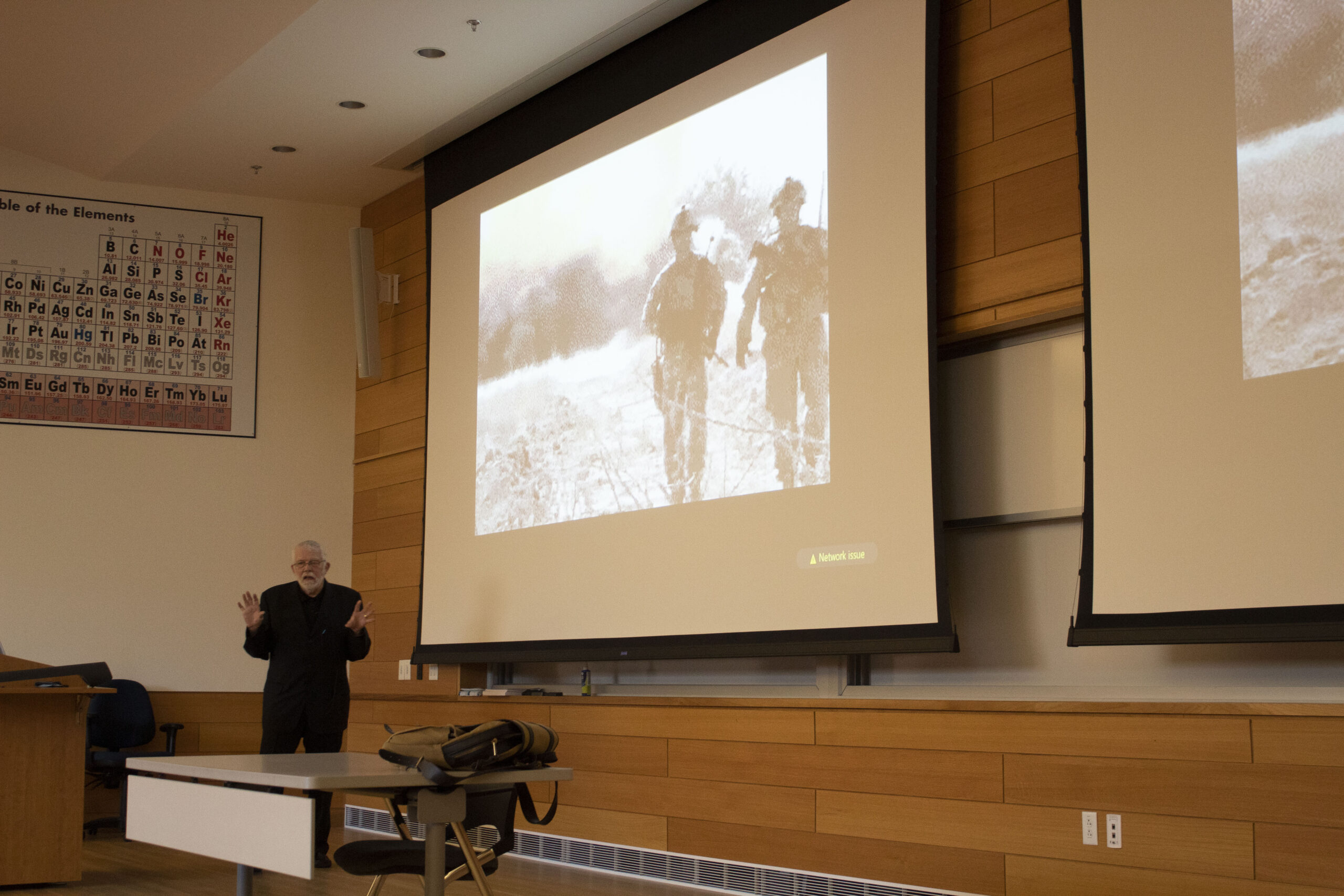

The director of the Rhode Island State Crime Laboratory discusses how the use of explosives in the military has changed over the past 100 years. PHOTO CREDIT: Hannah Charron | Staff Photographer

The University of Rhode Island hosted the second installment of the Forensic Science Seminar Series for the spring 2022 semester on Feb. 18.

The seminar, titled “Clinical Consequences of Chemical Explosions,” featured a talk about the clinical aspects of explosives by George Handel, a veteran who taught at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, a United States federal government health science university that prepares students for medical service to the United States.

Handel spent 30 years in the military in the Coast Guard before working for the Uniformed Services University, where he taught combat medical skills and deep-sea hardhat diving.

Handel talked about the increase of explosives used in combat and how explosives have changed the military in the last hundred years.

“Injuries from the 60s in combat were related to gunshot wounds,” Handel said. “Ninety-six percent were gunshot wounds. That’s reversed itself in the current conflict in Afghanistan and Iraq, where it’s 96 percent blast-related injuries. It’s quite a significant difference.”

Handel also explained the differences between primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary explosive injuries.

Primary injuries involve being exposed to the blast wave, a rush of pressure that expands outward from the center of an explosion. Secondary blast waves are penetrating and cause blunt force injury from debris and fragments released by the bomb. Tertiary injuries are the result of violent movement, involving force and penetrating injuries, and quaternary is a little bit of everything not mentioned in the other tiers, such as crush injuries, burns, and toxic fumes, according to Handel.

Explosives cause a “push-pull effect” where an initial blast wave goes out and the residual blast wind comes back. He said the safest place to be during an explosive blast wave is the ground.

“The blast wave is going to take the path of least resistance, so if you’re low, the blast wave will go over you,” Handel said. “Don’t try hiding behind anything, certainly don’t try running, unless you can run a mile a second.”

Handel explained other mediums that explosives can occur in, such as in water.

“Water is noncompressible,” Handel said. “An explosion that happens in the water is much more potent than a like-sized airburst, and travels further and causes more damage. The only safe haven for an explosion in water is to get out of the water.”

He also mentioned the moral dilemmas involved with aiding explosion victims, as most medical professionals are advised not to extract someone from rubble right away because it could shift the rubble and put others at risk. Handel said that the decision is difficult, but you have to make sure you make one you can live with.

“Somewhere along the line you’ve got to look at a mirror the next morning,” Handel said.

Fireworks are a more common and less threatening-looking explosive, but according to Handel, they’re just as dangerous.

“Firecrackers are an explosive,” Handel said. “They’re probably the most underestimated explosive on the planet, but they’re an explosive. And there’s high-order explosives and low-order explosives, but in reality, they’re all destructive.”

Handel said yearly there are around 10,000 injuries including blindness, limb loss, and even death because of fireworks..

“One of the most common things I would see a lot when I worked in California with the Marines, they would hold a firecracker and they would take bets on how long they could hold it before they throw it,” Handel said. “And of course, you know, they lose their fingers.”

Handel reminded everyone to chose the path of least resistance if ever in contact with a bomb, either far from the bomb, on the ground, or out of the water.

Dennis Hilliard, the Director of the Rhode Island State Crime Laboratory and an Adjunct Professor of Biomedical Sciences in the College of Pharmacy at URI, said the seminar series came about in 1999 to connect different departments at the University.

“We reached across all the spectrums of science-related students on campus,” Hilliard said. “Students benefit from the exposure.”

According to Hilliard, the University has hosted at least 12 guest speakers each semester involving chemistry, criminal justice, nursing, textiles, computer science and engineering since the first seminar in Fall 1999. COVID-19 has changed the structure of the seminars, but not entirely negatively.

“One positive thing about COVID-19 is that we are actually recording every seminar,” Hillard said. “so you can go back to Fall 2020 and see pretty much every seminar that was recorded.”

The Forensic Science Seminar Series showcases different speakers each Friday in the Spring 2022 semester, and the next seminar will be on Feb. 25 featuring Walter Williams and his talk on “Blood Evidence Before the Lab.”