Author, historian shares history of pre-NBA Black basketball players

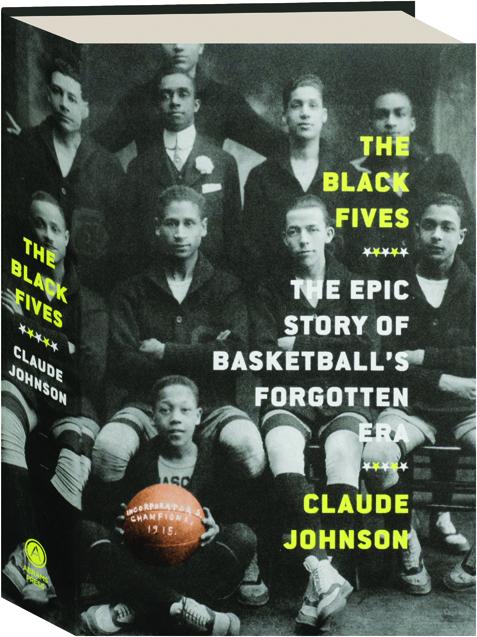

“The Black Fives: The Epic Story of Basketball’s Forgotten Era” researches, preserves and celebrates black history. PHOTO CREDIT: hamiltonbook.com

The Atlantic 10 commission on racial equity, diversity and inclusion presented a webinar about a new book titled “The Black Fives: The Epic Story of Basketball’s Forgotten Era” on Feb. 23, available to members of all 15 schools that are part of the A-10 conference.

Bernadette V. McGlade, a commissioner for A-10, welcomed over 200 virtual participants to the event. She introduced the co-chairs of the commission on racial equity, diversity and inclusion, the President of Duquesne University, Ken Gormley and the Vice President for Athletics and Recreation of LaSalle University, Brian Baptiste.

“It’s great to be here today to discuss some important history and enlighten all of us on the many strides that have been made throughout college basketball’s rich history,” Baptiste said. “Claude Johnson’s research into the lives of these young men and women, who were athletes more than a century ago, reminds us that we’re making a difference every day as we work toward diversity, equity and inclusion on all of our campuses and throughout our greater communities.”

Gormley said that this webinar is the third in a series hosted by A-10 for Black History Month and that they are thrilled to share the important, often overlooked, history and impact of African American basketball prior to the formation of the National Basketball Association (NBA), that set the foundations for basketball to become a professional sport in the United States.

The pair then introduced the speaker of the event, Claude Johnson, who is an author, historian and founder of the Black Fives Foundation, an organization with the mission to “research, preserve, showcase, teach and honor the pre-NBA history of African Americans in basketball,” according to their website.

Johnsons said that his book is inspired by his discovery of an 800-page NBA Encyclopedia in the 90s that “dedicated just three pages to African American basketball teams that had played prior to the league’s formation.” He then became dedicated to learning and sharing the deep history of African American men and women who played basketball across the country, publishing his novel and creating his foundation as a result.

“It’s [the book] narrative nonfiction,” Johnson said. “Which means we’re taking these pioneers and humanizing them. They weren’t just statistics, we want to find out who were they as people, what did their parents do, what was going on in society during this time?”

Johnson talked about the period of time before the creation of the NBA in 1946.

“I just started calling that period the ‘Black Fives Era,’” Johnson said. “Fives because of the five starting players. The Black Fives were these early pioneers, both men and women, and so this is a book about that whole story.”

He also talked about the importance of this history and the impacts it had on the game.

“It was important because this was a way of African American culture,” Johnson said. “Saying ‘we have something as well that we can contribute’ and they actually dominated most of the time, most of the games.”

Financial gain was another reason why basketball grew in popularity and why Black basketball players were welcomed to compete, according to Johnson. Their skills forced local teams they played with to get better and the more competitive a game the more financial benefit.

“[Black basketball teams] would go to a remote place that’s predominantly white, beat that local team, leave safely and come get invited back,” Johnson said. “And that’s because they were like a mobile economic stimulus that was bringing people in from miles around, during the Great Depression, during Jim Crow, and everyone was a winner, that’s why they kept getting invited back.”

One key player in Johnson’s novel is Cumberland Posey, who is most famously known for his career in baseball, but Johnson’s research and writings show that Posey was also an architect of the Black Fives basketball era.

Gormley talked with Posey’s great nephew, Evan Baker, a week prior to the webinar and shared a clip of their conversation.

Prior to his baseball career, Posey was one of, if not the, best basketball players in the U.S. in the 1920s, according to Gormley and Baker.

“I think the most important part of his basketball game was his ability to shoot the outside shot,” Baker said. “A precursor to the tremendous three-point shooters we have now, like Steph Curry. He shot from areas outside and kind of changed the game, forcing the defenders to come out and cover him.”

The pair said that Posey did ultimately get recognition for his accomplishments, but not while he was alive. Posey is currently the only person in both the baseball and basketball hall of fame.

After the clip of Gormely and Baker’s conversation, Johnson talked about women’s teams during this era.

“Women’s teams were there since the very beginning,” Johnson said. “The tradition was that the men’s teams, especially the club teams, would have a sister team.

He also talked about the roles men and women players undertook.

“The women also got involved in helping with the socializing after games on the men’s side, decorating and entertaining,” Johnson said. “But at the same time, the men, when it was their turn, did that for the women’s games. So they supported each other, because, after all, if you’re hosting a game it’s more than just the concept of ‘play then leave,’ hosting meant that you’re literally responsible for putting them up in hotels, the meals, the reception after the game — that was a really important part of it, win or lose.”

Johnson also said that hosting was a way to stay informed. He said there were very few people with phones and no internet to communicate, so going to games was social networking and a way to know what was going on around the country.

Talking more specifically about the “Black Fives Era,” Johnson said that the early times of this time were commonly playing against white teams on a routine basis before 1910.

“They didn’t mix teams, necessarily, but teams like the Smart Set athletics club in Brooklyn would play against their white opponents,” Johnson said. “And that led to this being normalized, honestly, even into the 1920s.”

Johnson also talked about the impacts those early teams had later on in basketball history.

“When the league first signed its first Black players, everyone already knew that African American talent was the best in the country,” Johnson said.

“Make history now” is the motto for the Black Fives Foundation, and Johnson said that the phrase has two meanings.

First is making history “cool” and relevant so that people today are interested in learning it, according to Johnson.

“The other meaning is that ‘make history now’ focuses on right now,” Johnson said. “So, the quality of what you put into this moment is directly gonna impact the future trajectory of what this moment ends up creating.”

Johnson said if you’re always worried about the next moment, you can never think about this moment.

Before concluding the webinar, Gormley and Johnson discussed the next steps for the Black fives’ story. Although Johnson is content with just “making history now,” he hopes that one day “The Black Fives: The Epic Story of Basketball’s Forgotten Era” can be turned into a documentary, motion picture and scripted series to broaden the reach of this story.