With the growing concern of global warming and pollution sitting heavy on communities’ shoulders, there is hope to be found yet in the Master Gardeners program at the University of Rhode Island.

The Master Gardeners are a group of volunteers that conduct many community outreach programs throughout the year, in connection with programs in surrounding states. One of their prominent community initiatives runs annually from March through October and is conducted with the aim of maintaining healthy soil and decreasing groundwater pollution in Rhode Island communities. This free service tests the pH of local soil and provides strategies to community residents to assist them with soil pH correcting.

Mary McNulty, a URI alumni and former chemistry teacher, has been with the Master Gardeners since 2015 and is now the central region soil test coordinator. She described the soil testing process as very accessible and effective.

“A lot of people are totally unaware that something as simple as a two minute test can be so beneficial and have such easy recommendations that anyone can do,” McNulty said.

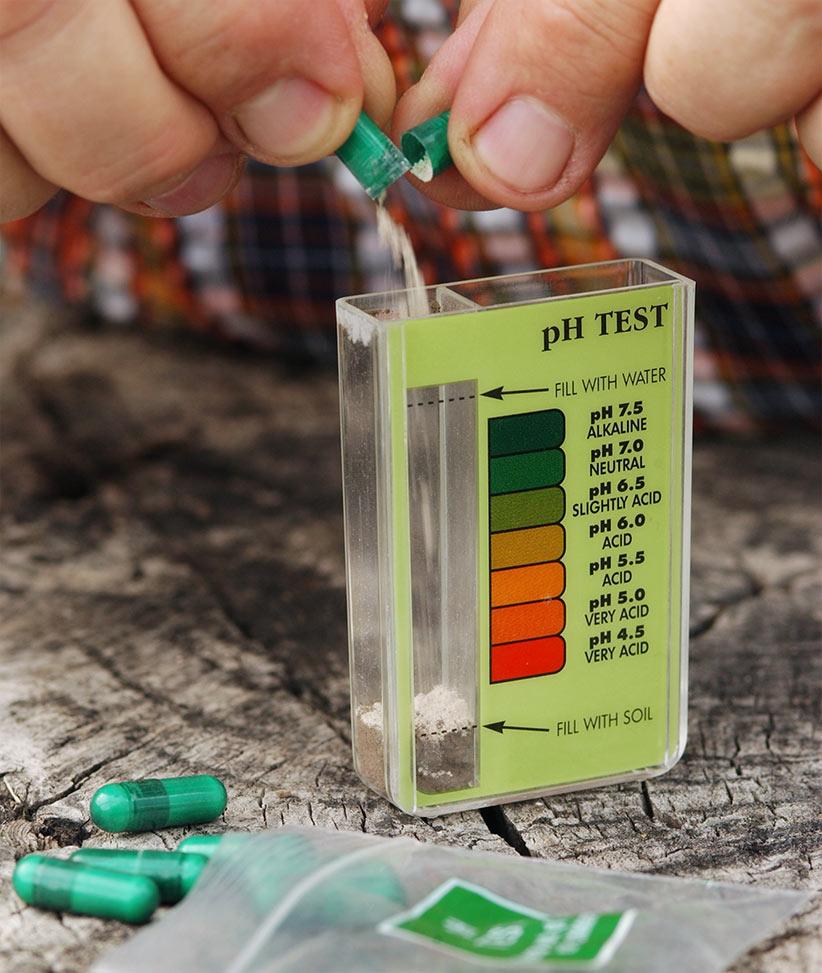

The test requires a cup of soil from individuals’ gardens within the community that the Master Gardeners’ sift to determine the soil’s texture. Then, they add distilled water to the soil and use a pH probe to determine the current pH of the soil. From there, depending on the kind of plants the individual wants to grow in their soil, different amounts of lime (composed of calcium carbonate) or various nutrients can be added to the soil gradually under the assistance of the program.

“More and more people are coming out and getting their soil tested,” McNulty expressed, describing the trust the outreach program has gained in the community throughout the years. The Master Gardeners’ primary goal with this initiative is to educate people within the community and help them build better and more sustainable gardens over time, in a way that avoids damaging the ecosystem.

McNulty also explained how the difference in acidity between pH levels is much larger than people expect.

“If you want to go from a [pH of] 7 to a 4, in say a year, you’re going to put all the microorganisms in the soil into toxic shock,” She said.

The process of pH correction takes time, sometimes years depending on the starting pH and the desired ending pH, but the slow process allows for organisms that help plants to adjust to the changes.

“If I have seen anything over the years, I have seen more college students get involved, and that is so wonderful,” McNulty said.

This much is clear through Madison Tiner, a fourth-year student intern with the Master Gardeners program studying biological science. Tiner works primarily in cooperative extension within the program as an intern and helps plan community outreach events.

“It feels super impactful to be a part of this internship,” Tiner said. “One of our main purposes for cooperative extension is to help share scientific based research with communities.”

Master Gardeners set up at various farmers’ markets and libraries throughout the year, where community members can come to get their soil tested. There is also the option to mail in soil samples if making the trip is difficult, and the program can even connect community members with services that do more in depth testing if desired. Looking toward the future, Tiner hopes that the initiatives of Master Gardeners increases accessibility to knowledge and information to beyond URI students.

The Master Gardeners, being volunteers, conduct an annual core training program in the Spring for community members to learn how to become Master Gardener volunteers. Within this yearly program, they take three to four student interns to help teach the training, which can count for academic credits and will be opening for application in the coming weeks.

Master Gardener initiatives such as local pH testing as well as the food recovery for Rhode Island program, currently going on as well, seem to be having large impacts on surrounding communities as discussions around the health of the planet and of people are on the up. With the goal of collaborative education, an environment with less pollution, cleaner water and food and a stronger community bond is on the horizon.