It’s impossible to check your social media without being bombarded by posts from various sites relating to your horoscope, your breakfast order, open letters to your best friends and thoughts you have while existing.

Pieces like those have a place online. They’re entertaining and relatable, and are often thought provoking. There’s nothing wrong with writing or enjoying open letters, quizzes, etc. but by no means is this content journalism.

The point of this column is not to undermine any of these sites or posts. We’re two journalism majors and we’re just perturbed that these blog posts are being called journalism, because they aren’t.

Journalism is not about “an open letter to my ex-boyfriend” or “10 reasons you know you’re obsessed with The Office.” Sure, these pieces are published online, but they’re not newsworthy. By this, we aren’t just talking about breaking stories covering death or crime. Newsworthy content is anything that affects or is important to the reader. Newspapers have features, entertainment, opinion and sports sections that contain the same elements that news stories have, just in specific categories.

The difference is, journalism is on a need to know basis.

Newsworthy topics are pertinent, relevant, and can be thought provoking. Top 10 lists, open letters and the like are blog posts with little supervision, reposted on social media. Writers they may be, but there is no way to compare them to journalists. We’re here to set the record straight, and you can quote us on that.

Some people may think journalism is “easy.” It may seem like journalists just slap some thoughts on a piece of paper, but that’s not how it works. Journalism is all about facts, and while we do have an opinions section, we criticize responsibly and offer solutions to problems we see.

As reporters, we research and interview people each week, which requires setting up a date and time to meet in person, coming up with intriguing questions, logging the interview afterward and then actually writing the article.

Before it is published online and in print, the article must go through an online proofreading service and passed through different editors. After it’s published, the piece is not only an article, but a story that is published alongside other journalistically sound pieces in a print newspaper or online publication.

Journalists have training in their field, they’re not just anyone with a computer. At the University of Rhode Island, all journalism students are required to take JOR 115: Foundations of American Journalism. It’s in this class where we learn journalism’s role in our society: to provide unbiased facts about our government and report them back to the people. Journalists are the unofficial “fourth estate” and provide a working role in democracy so citizens can make educated decisions about who they put into office.

In order to do this effectively, journalists follow a code of ethics to ensure that reporting is unbiased, factual and holds merit. We avoid conflicts of interest by reporting on events and people we don’t know, and use copy editors to double check our facts.

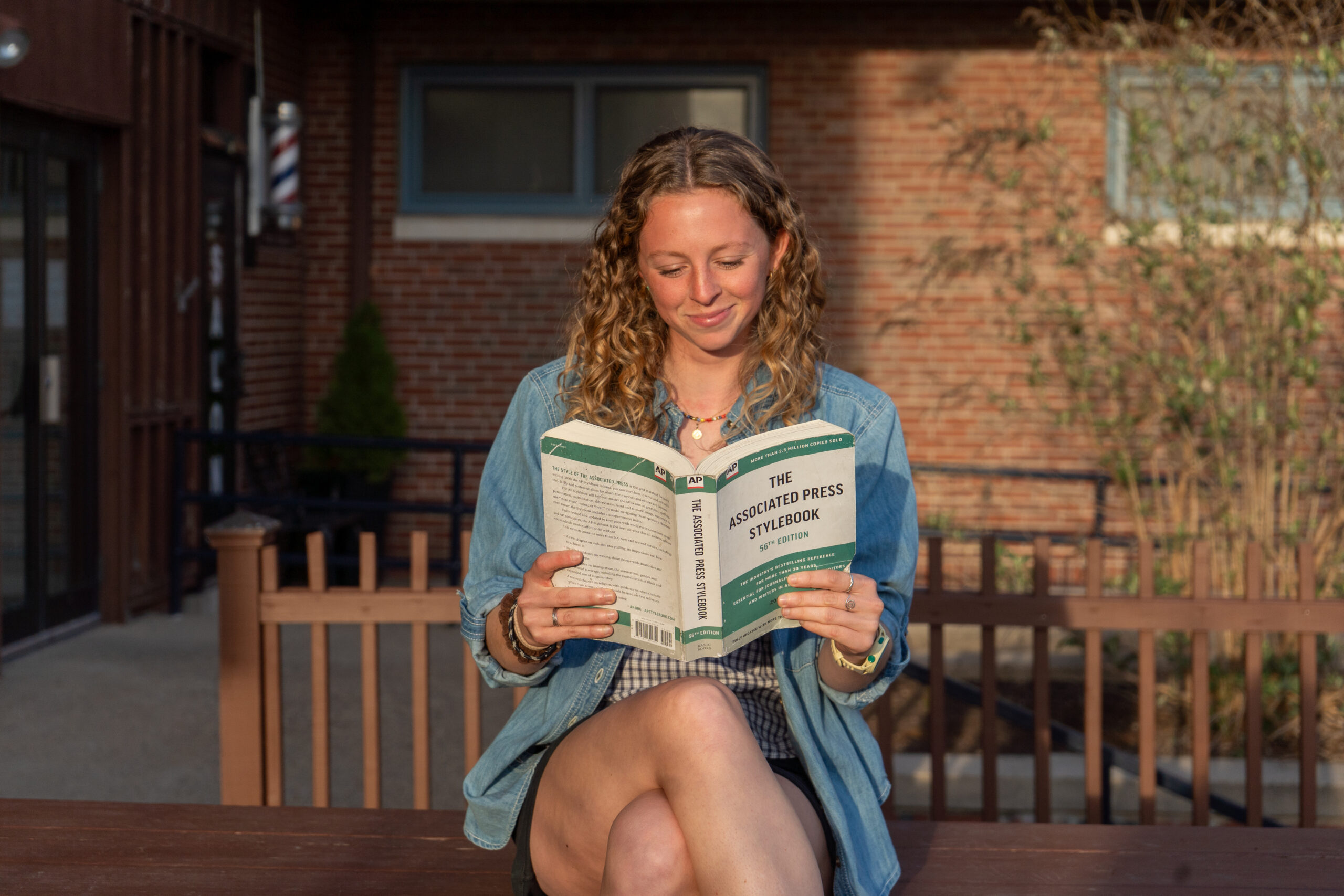

Not only do we work ethically, but we also follow a style. Unlike regular academic or creative writing, journalists must follow “The Associated Press Stylebook,” a set of rules and stylistic entities that ensure consistency across publications. It’s technical formatting, and each article must be written a certain way and include certain punctuation, grammar and specific abbreviations.

Just because you identify as a journalist doesn’t mean that every single piece you write is going to be considered journalistic. It is possible to be a journalist and write for those sites. However, don’t confuse two very different kinds of writing. Your choice in footwear and how it relates to your personality does not fall under any of the guidelines that determine newsworthy content.

The difference between an article and a blogpost is the work in the background; the content, research, writing, editing and ethics that are ingrained into each and every journalistic article. That’s what makes us inherently angry as journalists. You’re treating all of the content the same. If the New York Times started posting “101 reasons your BFF’s house will always be your home away from home” would you still call it news? Our guess is probably not.

So, to stop this confusion, we suggest that people think about what they’re reading online. If you’re reading a story full of gifs, “100 reasons why” posts, open letters and quizzes, that’s fine, but just know that these are blog posts. They’re not newsworthy and they’re not always thoroughly edited.

We want to make clear that there is a distinct difference between these posts and journalistic articles because at the end of the day, we put a lot of work into what we do, and we’d like to be properly credited.