Graphic from uri.edu/cfrp.

University of Rhode Island students and faculty are working to educate the public about another national health crisis the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated: the opioid epidemic.

Last year, URI received a $1.1 million grant from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to address the opioid crisis in rural areas for two years. Pharmacy professor Anita Jacobson, nursing professor Diane Martins and natural resources science professor Deborah Sheely have used the grant to create the Community First Responder Program (CFRP).

The CFRP travels across rural areas of Rhode Island that are particularly vulnerable to the opioid crisis to educate communities about substance abuse and opioid misuse. They teach communities the signs of an overdose and how to respond, utilizing the naloxone kits they distribute as well.

But according to Jacobson and Martins, the COVID-19 pandemic has made the opioid crisis worse than it was before. Although the grant was awarded before the pandemic, Jacobson explained that it is needed more than ever. There has been an increase in overdose deaths since March when pandemic lockdowns began, with a record 40 overdose deaths in Rhode Island in July, according to Jacobson.

“Certainly we are seeing mental health and substance use disorder issues affecting rural communities in particular, related to economic impact,” Jacobson said. “And now that’s been exacerbated with the pandemic.”

Because of the pandemic, the CFRP had to adjust. They set up information booths at public events such as farmer’s markets, albeit socially distanced, where they also give out naloxone kits and fentanyl test strips. The program no longer has access to URI’s Mobile Health Unit because its small size did not meet social distancing standards, which Jacobson said was a challenge.

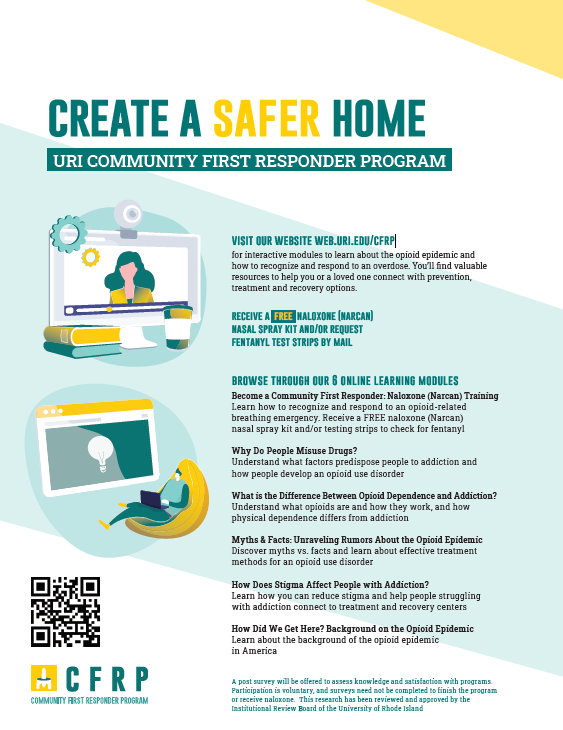

Instead of holding in-person community seminars, particularly at schools and other public buildings, Jacobson and Martins said they’ve held group sessions online over WebEx, in addition to asynchronous learning modules online. These can be accessed at https://web.uri.edu/cfrp/.

Jacobson said that having these events online actually improved the CFRP’s numbers. She said that some webinars had up to 100 people in attendance, and feels that despite the change, overall it went well.

“I think if anything, it may have improved our numbers by being online,” Jacobson said. “It just was different. It wasn’t what we envisioned doing, we planned to be sort of in person out in the community, but there’s no way to have a crystal ball to know how it would have gone.”

Both Martins and Jacobson said that many people who come to the project’s booths or events share stories of loved one who suffered from opioid addiction. One example Jacobson gave was of a person who came to a booth one week but was hesitant to take a kit. However, the same person came back the next week and took a kit because one of her friends had actually used one to save someone from an opioid overdose.

Martins noted that much of the program’s work involves ending the stigma regarding opioid addiction. She said that earlier in her career, she’s had people tell her that people with addictions deserved to die, so through the educational component of the CFRP, she hopes to illustrate that addiction is an illness, not a moral failing. As a longtime public health nurse, she said that many vulnerable populations such as the incarcerated and the homeless are more likely to struggle with addiction.

“I’m glad people are recognizing that we need to do other things to help this,” Martins said. “I’ve also worked with the homeless. The chance of people who are homeless having substance abuse is high. I think the biggest thing to me was trying to work on stigma and work on reducing stigma for people who are homeless.”

About 20 students across various disciplines are involved in the project, according to Martins. Kendra Walsh, a sixth-year pharmacy student, was one of the first students to get involved after Anderson contacted her specifically for the project. Last year she, Jacobson and classmate Allie Lindo helped create the educational modules on the program’s website, as well as hosting presentations and outreach events. Ever since the pandemic, Walsh has continued outdoor outreach and online presentations, including one with some staff from URI Health Services.

Hailing from Wyoming, Rhode Island, a rural village in Richmond with a population of about 270 people, Walsh said she knew someone who died of an opioid overdose. She explained that going out in the field helped her understand how to apply what she’s learned in her classes.

“It’s been impactful for seeing a different perspective,” Walsh said. “We learn about opioids and substance use disorders in pharmacy school and other topics related to medication safety, but to really talk with people who have been so impacted by addiction in their families, it’s very humbling to make an impact in others lives. You have a changed perspective after working with people who have these struggles.”

Walsh said that moving forward, the CFRP will move towards more online sessions since the weather is getting too cold for outdoor events.

In the future, Jacobson said she hopes to collaborate with local police departments to give them “leave behind” naloxone kits. Leave behind kits are narcan kits first responders can give the family members of people who’ve overdosed after an incident. The family members can utilize the kits in case their loved one overdoses again.

Martins said she’d like to set up “safe stations” in rural fire departments similar to those in Providence, in which someone can receive beginning treatment for opioid addiction. However, Martins acknowledged that this may be difficult since many rural fire departments are small or run by volunteers.

She also emphasized that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic made addressing the opioid epidemic more important than ever.

“It feels very hopeful, even though the opioid epidemic in Rhode Island is really accelerating, especially during COVID-19,” Martins said. “I have a relative who died of an overdose during COVID-19, and I know part of it is the conditions of COVID-19 making it higher risk for people to overdose, I’m happy that we could do something to make a difference.”