Marta Gomez-Chiarri hopes to stabilize oyster hatcheries

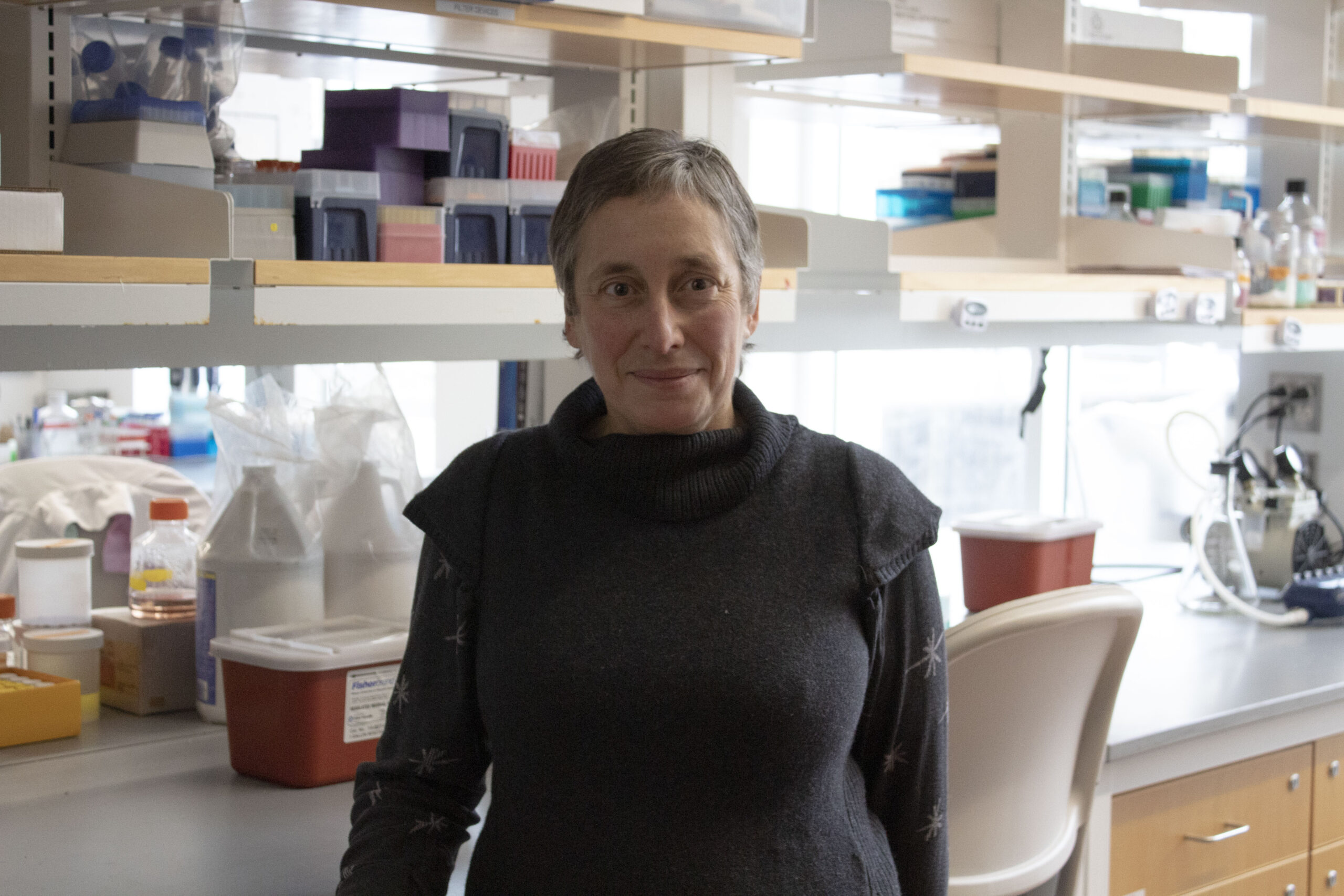

Marta Gomez-Chiarri, a professor of fisheries, animal and veterinary sciences, is researching microbes to promote stability in oyster hatcheries. PHOTO CREDIT: Hannah Charron | Staff Photographer

Marta Gomez-Chiarri, a professor of fisheries, animal and veterinary sciences at the University of Rhode Island, said that her love of the ocean and its creatures originated in her childhood.

Gomez-Chiarri, born in Madrid, grew up in Galicia, Spain along the Atlantic coastline. According to her, the town relies heavily on its fishing production.

She received her bachelor’s degree and doctorate in biochemistry and molecular biology from the Universidad Complutense in Madrid. Before coming to Rhode Island in 1997, she also worked as a research fellow at the Stanford University Hopkins Marine Station.

Her research started by researching the immune system’s response to kidney disease in both humans and rats, before moving into the field of marine biology to continue her research.

While at Stanford, Gomez-Chiarri studied abalone, a type of large marine gastropod, akin to slugs and snails.

“It has a very beautiful shell that is used for jewelry and it’s very expensive,” Gomez-Chiarri said. “The populations of abalone in California were being depleted because of the fisheries and it is a highly valued species but it grows very slowly.”

Due to this, she went on to develop methods to understand how to genetically modify those organisms in Africa in controlled systems. After that, Gomez-Chiarri moved to another postdoctoral fellowship working on creating vaccines for diseases in trout communities before coming to URI to study similar concepts in the Atlantic Ocean.

According to Gomez-Chiarri, even though the process of creating vaccines and solutions for diseases in marine animals is similar to the process of doing so for humans, the types of diseases are not often the same.

“All organism’s basic methods of disease are very similar,” she said. “In general, diseases in animals, like oysters, are caused by different pathogens. The pathogens are different from humans because they live in different environments.”

Though the pathogens are different, Gomez-Chiarri said that even the process of giving fish vaccines is often similar to that of humans. She explained that injecting the fish with vaccines into their bloodstream is one of the most difficult parts of her job. According to her, occasionally fish are also immersed in water that is saturated with a vaccine instead of injecting them.

David Rowley, a professor of pharmacy at URI who works closely with Gomez-Chiarri, said that diseases in fin and shellfish are one of the greatest threats in the seafood market.

“In order to meet the seafood demand for everyone on the planet who desires to have seafood as a meal, we can no longer rely upon wild-caught harvests,” Rowley said. “There just aren’t enough fish and shellfish in the marine environment in order to fulfill all of the demands, so we’re having to rely more on aquaculture in order to produce sufficient seafood.”

Disease is one of the greatest threats to aquaculture as well, according to Rowley. He mostly focuses on the development of an antibiotic for these marine creatures in order to combat bacterial diseases.

Rowley contributes to the development of these antibiotics through the study of molecules created by marine microorganisms. He studies how these organisms interact with other microbes in order to thrive in their environment. According to him, this can be copied to help prevent disease.

Rowley said that one organism that is often affected by diseases is oyster larvae.

“A lot of people, when they get an oyster to enjoy at a restaurant in the local area, they don’t often think about where that oyster started,” said Rowley. “The fact that it started in the local marine environments that we have here and in Rhode Island and beyond and that this entire industry is reliant upon our ability to successfully cultivate oyster larvae – it’s something that we’re proud of and we need to take care in the approaches to make sure that we can continue to have these delicious oysters to enjoy.”

Rowley said that currently, researchers of these topics, like himself and Gomez-Chiarri have figured out how to cultivate a microbe in large quantities to promote stability in oyster hatcheries and are working on licensing and selling this microorganism to a company in order to create a product right now.