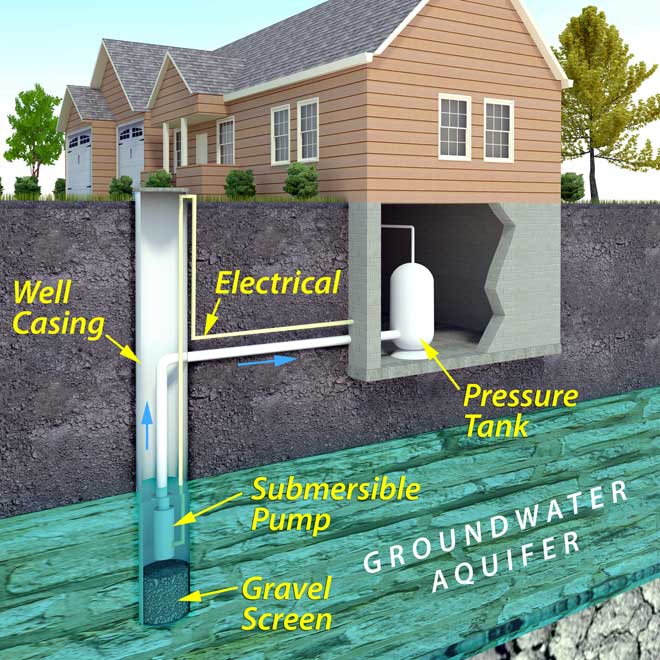

URI Cooperative Extension holds a virtual workshop to explain the importance of water well maintenance and the dangers when wells go unmanaged. PHOTO CREDIT: Home Reference

Wells are a cost-effective way to deliver water to your home with long lifespans, and the University of Rhode Island’s Cooperative Extension held a virtual private well water workshop on March 22 to educate the community about maintaining private wells and keeping well water safe to consume.

Molly Allard, the outreach and education program manager at the Northern Rhode Island Conservation District (NRICD), started the workshop by talking about the NRICD’s mission in helping Rhode Islanders conserve natural resources, like soil and water.

“We like to talk to residents about how they can take care of and produce their own drinking water,” Allard said.

Alyson McCann, water quality program coordinator at the University of Rhode Island Cooperative Extension, started her presentation about private well water with the science behind wells and the groundwater used for wells.

“Groundwater is part of our water cycle so as water moves through the water cycle, as you know, falling to the ground as rain, or freezing rain or snow,” McCann said. “It can run off into surface water bodies. It can also move down through the soil profile and infiltrate through the soil and recharge the groundwater system and it’s into this groundwater system that we put are private wells.”

McCann said the quality of the groundwater is affected by what you do in and around the wells including how we use, store and dispose of potentially hazardous chemicals and what is in the soil and rock that the groundwater moves through. Areas where apple orchards currently or previously resided, for example, could hold arsenic in the ground, so researching and testing the surrounding area is important.

“We have some naturally occurring substances that can affect our well water quality,” McCann said. “It can affect the taste, the smell, the color of the water, the clarity of the water and in some circumstances, naturally occurring substances could also affect our health and whether the quality is safe to drink.”

She said that there are many practices to ensure safe drinking water, including keeping distances from potential sources of contamination. McCann recommended keeping wells 100 feet away from septic systems and animals, 50 feet away from sewer lines and septic tanks and 25 feet away from roads.

Low maintenance grass is also recommended, including the use of minimal pesticides and no decorative coverings, plants or shrubs on or near the well.

“[Decorative coverings and greenery] could encourage rodents to live near the well,” McCann said. “Where they could burrow near the well they could, you know, potentially get into the well.”

McCann also talked about the three different well structures: drilled wells, driven wells and dug wells. Drilled wells are drilled by machines into hundreds of feet of bedrock. Driven wells are down sand and gravel, shallower than drilled wells at around 100 feet. Dug wells are the shallowest of the three, at only nearly 30 feet deep.

McCann said people should test their wells at state-certified labs if they have flooded, if the color, taste, or smell of the well water has changed and once annually to keep track of water quality over time and to see if treatment is necessary.

“Treatment is something that really there’s a lot to talk about in treatment and it really depends on the test results,” McCann said.

She said that there are two treatment types; a point-of-use treatment and whole-house treatment. A point-of-use treatment treats water coming out of the tap for taste, odor and other substances that were found in the water from testing. Whole House treatment treats all of the water in the house through filters in the basement that remove particles, sediments, sands and gravels

McCann ended the workshop with four ideas to take away from her presentation: to learn, protect, test and act on your well and its conditions.