Linda Lotridge Levin pioneers path for women in journalism

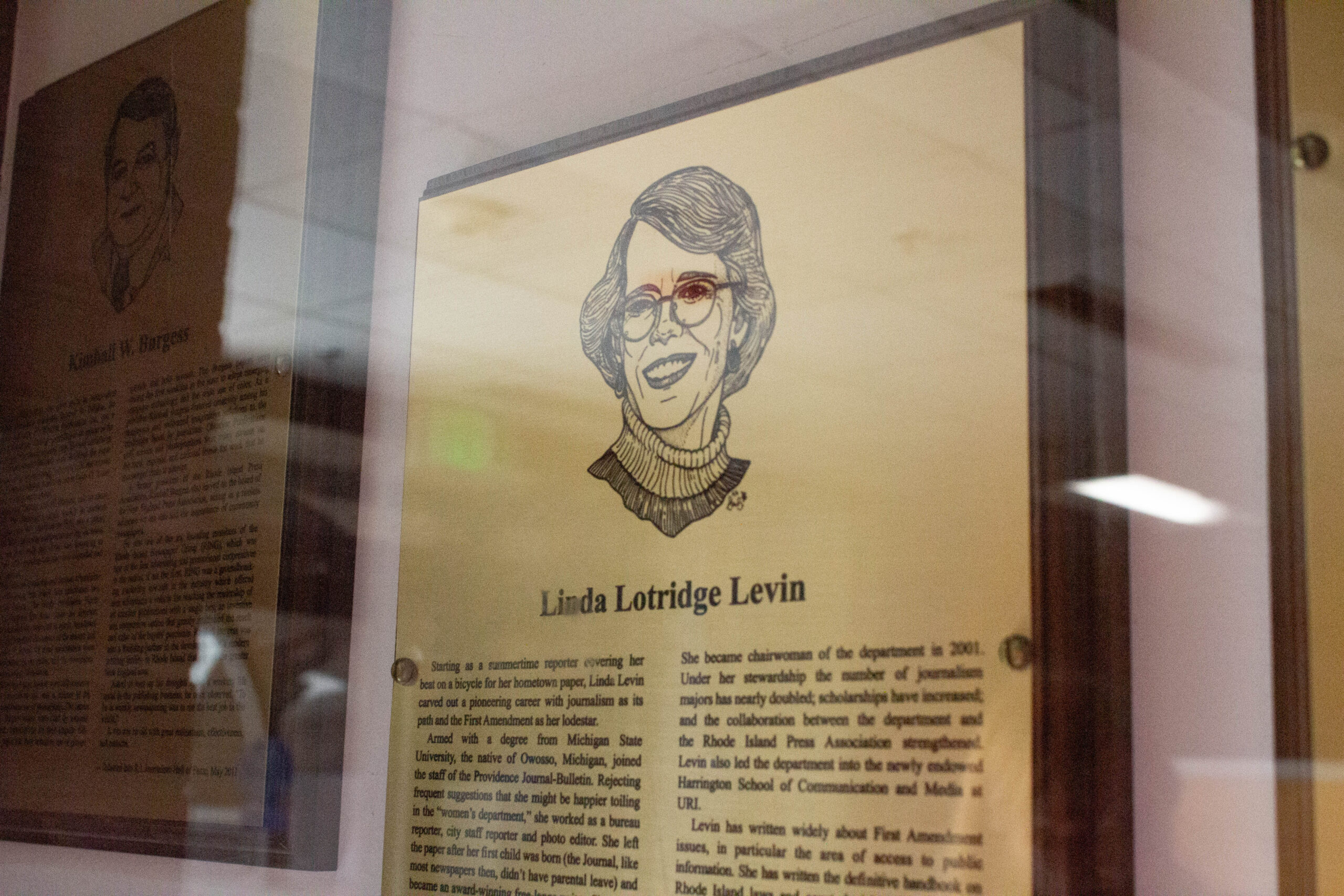

After being inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame, journalism professor emerita Linda Lotridge Levin shares her story, reflects on her career and talks about the lives she touched. PHOTO CREDIT: Maddie Bataille | Photo Editor

URI professor of journalism emerita, Linda Lotridge Levin, has been “a pioneer” for women in journalism throughout her profession, paving the way for many young journalists.

This comes according to Shane Donaldson, a member of URI’s athletic new media and communications team, and a former student of Levin’s. Donaldson graduated from URI in 1999.

Levin will be inducted into the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame on April 29 and will be recognized for her work as a reporter and impact on others.

This isn’t the first honor Levin has received for her work as a journalist. She has held a spot in both the Rhode Island Journalism Hall of Fame and the Academy of New England Journalists for about 15 years.

Originally from Owosso, Michigan, Levin received her undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan and made her way East to receive her graduate degree at Boston University.

Levin started her career in reporting at The Providence Journal, taking stories about anything she could get her hands on. These stories included covering the General Assembly, police beats, political news and features.

However, Levin mentioned that some of her favorite stories included getting the chance to interview the nephew of Winston Churchill, a private secretary during World War II and the Second Lady of the United States.

“I did all kinds of stories,” Levin said, looking back upon the chances to meet these people.

But even with great interviews like these, Levin had to endure a lot of push back as a woman in journalism.

“I worked very hard,” Levin said. “I love my work and I put up with a lot of harassment.”

Her drive pushed her through the difficult time of navigating what Levin said was “a man’s world.” For Levin, it paid off, not only for her career, but for her personal life as well.

Levin met her husband of 55 years during their time working at the Providence Journal. They worked side-by-side until Levin left to have their baby daughter, and since there was no maternity leave at the time, Levin ended her career at The Providence Journal.

When she was ready to look for work again, Linda had to start her career all over.

She began freelance writing, contributing to The Boston Globe on the topics of health and medicine. Her work won her an award for this writing, which gave her the opportunity to have a nationally syndicated health and medicine column in newspapers throughout the country.

Levin said amidst all of that, URI asked her to teach some journalism classes starting in the early 1980s.

“When I arrived there, the department was all men,” Levin said. “[There were] a lot of challenges as a female working at URI in the journalism field.”

Still, she made light of the hard work she was enduring. Levin told a story of the first faculty meeting she attended when she arrived.

“They were all men, and they all had beards,” Levin said. “I went out and bought a fake beard, black and bushy and I wore it to the meeting.”

Her goal before she left URI was to bring more women into the department. Levin proudly said the women she got to work with over her time “have crashed through the glass ceilings,” as she has noticed more women taking on higher positions.

During her time, Linda Lotrige Levin touched the lives of her students.

“She was really tough on me but in the most caring way,” Donaldson said.

Donaldson told a story of his most prevalent memory over the time he had her. One morning during his sophomore year, Donaldson walked into class and was greeted by Levin, who said, “you’re dead meat.”

Donaldson, who was terrified as to why, said that Levin explained to him she had worked with his grandfather at The Providence Journal years before.

Barney Madden was the sports editor of The Providence Journal, the grandfather of Shane Donaldson and, according to Donaldson, the reason he wanted to study journalism.

Levin said that the grandson of Barney Madden was not “going to float by” in her class.

Madden was a close friend to Levin, and one of the men at the journal who didn’t treat her as a lesser person. According to Donaldson, that morning was a turning point.

“She was the reason I have been able to sustain a career in journalism,” he said.

In regard to aspiring journalists and the structure of the profession evolving, Levin said, “there will always be journalism, it’s just going to present itself to the consumer in a different way.”