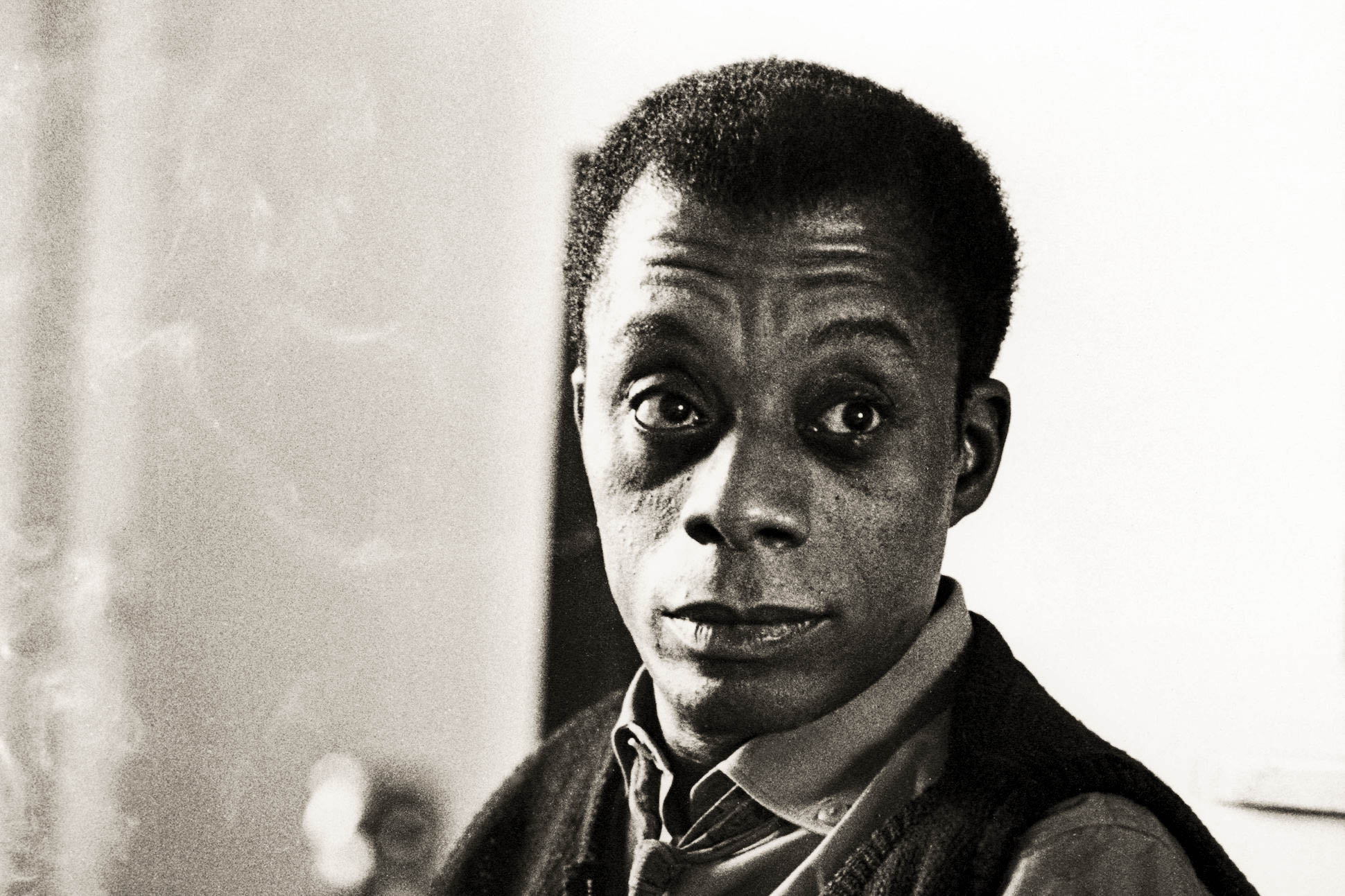

James Baldwin, a Black man born in Harlem, New York on Aug. 2, 1924, was a prolific author, essayist and playwright on issues of racial justice, religion and homosexuality.

I was first exposed to his work in my third year of high school when I read “The Fire Next Time,” which contained two essays by Baldwin. “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind” – an essay within the book – was about Baldwin’s experience as a youth pastor and how religion connected to his race and sexual identity.

I was deeply moved by his words. His style of writing was captivating and thoughtful; I was instantly drawn in. The reader gets a glimpse into young Baldwin’s god-fearing mindset; God did not bring comfort to him but pain.

“All I really remember is the pain, the unspeakable pain; it was as though I were yelling up to Heaven and Heaven would not hear me,” Baldwin said in the essay.

I was instantly hooked on his work and went on to read “Notes of a Native Son” and his other works I could find for free online. I am currently reading one of his novels, “Giovanni’s Room.”

Baldwin spoke about his experiences as a Black, queer man quite often and how his sexuality and race intertwined. An interview between Baldwin and Richard Goldstein revealed a lot of his feelings about being gay and Black in America.

In this interview, Baldwin states how many white gay people feel ostracized from heterosexual whites because they feel cheated out of the advantages that most white people accrue in society. This makes them distinct from Black gay people, who have been ostracized for their race their entire lives, and being gay makes them even more vulnerable.

Baldwin still believed that gay rights movements, which were largely composed of white people at the time, and the Civil Rights movement could coalesce. Both of these groups have experienced oppression from those who feared their prosperity, which Baldwin thought would help the groups find common ground.

In the modern era, LGBTQ+ movements are more intersectional and include more queer people of color in their activism. However, this could definitely be improved upon, and LGBTQ+ rights groups and organizations should consider Baldwin’s words.

Baldwin writes with a vividness for emotion that I had not seen before. He understood what it meant to be human and how systemic racism has dehumanized us. I saw this especially in an excerpt from “Notes from a Native Son” when he talks about his father.

Once his father passed away, he was able to see him not as the domineering figure he was in his past, but a frightened, frail man. The bitterness and anger that his father had is something that Baldwin carried too, and he had to find a way to cope with it.

When referring to his hatred towards his father, Baldwin said:

“I imagine that one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain.”