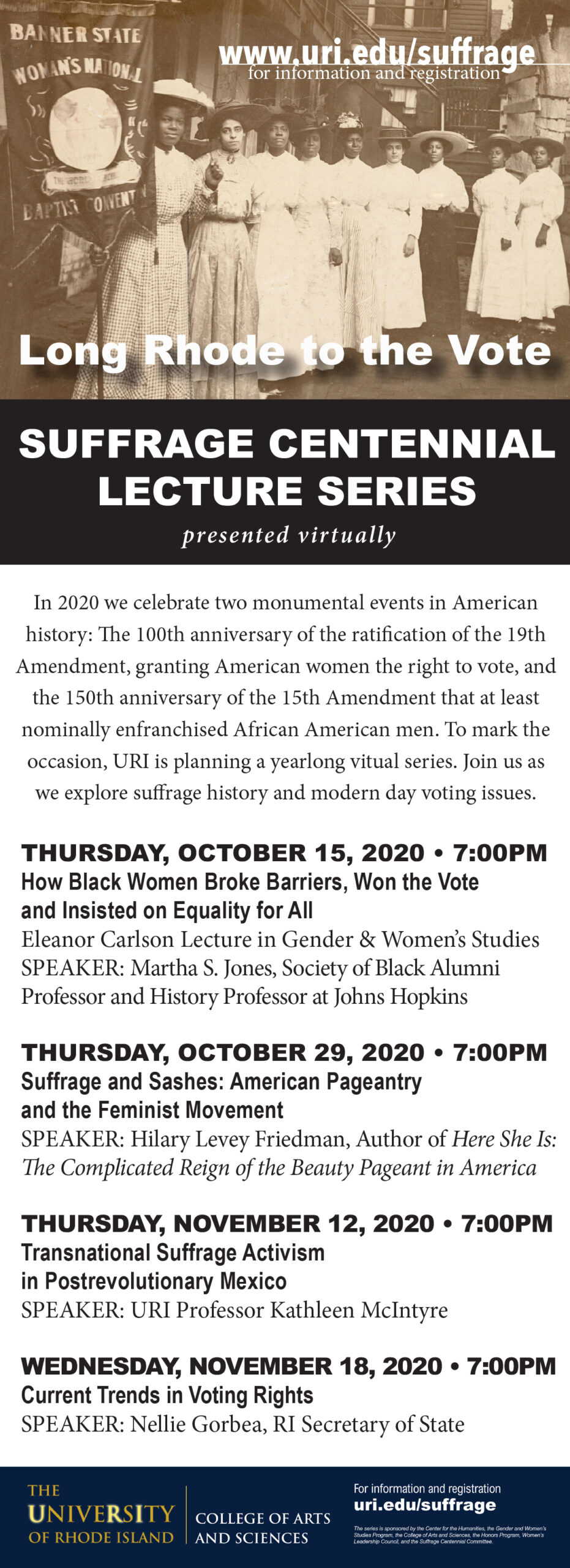

Award-winning historian Martha Jones speaks in second Long Rhode to Vote lecture

Martha S. Jones discusses the historical barriers against Black female voters. Photo contributed by Kayla Laguerre-Lewis.

“This is indeed a time when we must understand the historical perspectives related to women’s suffrage and civil rights, that form frankly, the underpinnings of democracy,” Provost Donald DeHayes said. “And we must insist for voter equality for all regardless of who we are and what we stand for.”

DeHayses spoke to introduce award-winning historian, writer and commentator Martha Jones, who was the second speaker for Long Rhode to Vote, the suffrage centennial lecture series organized by the University of Rhode Island’s Center for the Humanities in cooperation with the gender and women’s studies program. Her Oct. 15 lecture was titled after her 2020 book of the same name, “How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote and Insisted on Equality for All.”

100 years after the passage of the 19th Amendment, Jones pointed out that there are two myths commonly believed to be true surrounding it: all women won the vote, and American women were guaranteed the vote.

The amendment did protect women from voter discrimination on the basis of sex, but other state laws around age, citizenship, residency, mental competence and more kept them from the polls. Before 1920, Black women had been voting from passages of state laws in places like California, Illinois and New York, but there was still a long way to go in actually securing the vote for all. This is what Jones said keeps her from celebrating the centennial, since many factors prevented women of color from achieving full suffrage at the time.

“When we appreciate what an open secret Black women’s disenfranchisement was in 1920, the facts of the 19th Amendment fit only awkwardly with events that feature light shows, period costumes and marching bands,” Jones said.

Jones acknowledged that while the country is not yet at a point of celebration after 100 years, there has been progress that would have been seen as potentially unimaginable by the Vanguard, a group of women that she named in her book and talk.

The Vanguard was a group of women who organized and fought for voting rights for African Americans and equality for all, which culminated in the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Perhaps there is not a more prominent example of this progress than Senator Kamala Harris, who mentioned the women of the Vanguard in her Democratic vice presidential nomination acceptance speech: Mary Church Terrell, Ida B. Wells, Mary McLeod Bethune, Diane Nash, Fannie Lou Hamer and Constance Baker Motley.

“Collectively, the story that our ballots this year tell is that nearly 130 African American women are running for Congress in 2020,” Jones said, which shatters the record of 48 set in 2016. “Black women are no longer merely firsts on the political scene, they are really situating themselves as a force in Washington.”

It took 100 years to get to this point; 100 years of what Jones called the “nitty-gritty work” of the ground game, which included registering to vote, attempting to cast ballots and showing up and out to the polls in large numbers, collectively, as Black women.

The ground game turned into a legal campaign, led mostly by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) through lobbying and litigation that worked to chip away at the edifice of voter suppression that became part of Jim Crow. Then emerged the modern civil rights movement in which leaders such as Diane Nash, Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker were joined by hundreds of thousands of Black women across the American South.

Jones noted that Black women activists of 1920 understood at the time that politics was a long game, and many, like Bethune, would not live to see the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“They [were] prepared to train, to pass on, to inspire and to otherwise press the next generations, including our own, to continue to do the work of democracy, including that of voting rights,” Jones said. “With the admonition that we follow in their model and do the work for our own time, but also lay the foundation for the work to come.”

The work of our time and the work to come still revolves around voter suppression, according to Jones, which did not end in 1965 and is shown in 2020 through voter intimidation, gerrymandering, shuttering of polling places, voter ID laws and the unwillingness or inability of local officials to guarantee health and safety amid the pandemic. Still, there are images of long lines in which people wait for hours, knowing that there is some force out there that will keep them from casting their vote if they don’t.

“There is a kind of complacency, there is a sense that we have a right to vote, which in fact we don’t, at least constitutionally speaking; the sense that voting is sort of a routine and a ritual without much substance,” Jones said. “Nobody is a better advocate for why we should vote [than] someone who has had their vote taken away.”

Jones said that we can learn something through looking at the past and the disenfranchisement that took place; a past in which Black women worked together against racism, sexism, intimidation, discrimination and harm to get to the polls and help others do the same. One force that they often had to fight against was other women, specifically white women suffragists, who used anti-Black racism as a tactic in the 20th century to get the support of southern white women. Jones called the divide a missed opportunity for the women to link arms and really transform the landscape for all in 1920.

She attributed the fact that white women were often witness to and failed to intervene when they saw Black women being denigrated, derided, assaulted and worse. It is a divide that still persists today and leaves the country with further moral dilemmas as we try to grapple with the lack of progress and celebrate what progress has been made in this election cycle.

“As we decry, we protest and we mourn the killing of a young woman like Breonna Taylor, we are also in a moment where we can hold up, engage and perhaps even celebrate the candidacy of Kamala Harris; what a complicated occasion for all Americans to grapple with in 2020,” she said. “I think it is the necessary dilemma and that we have to grapple with all of that in our own lifetimes rather than reduce ourselves or our politics to one or the other side of the equation.”