James Young discusses the vernacular of memorials at the first event for the Center for the Humanities’ lecture series, “Memorials and Commemoration in the U.S.” PHOTO CREDIT: uri.edu

From Maya Lin’s 1982 Vietnam Veterans War memorial to Bryan Stephenson’s 2018 National Memorial for Peace and Justice, James Young believes there is what he describes a “trajectory of memorial vernaculars.”

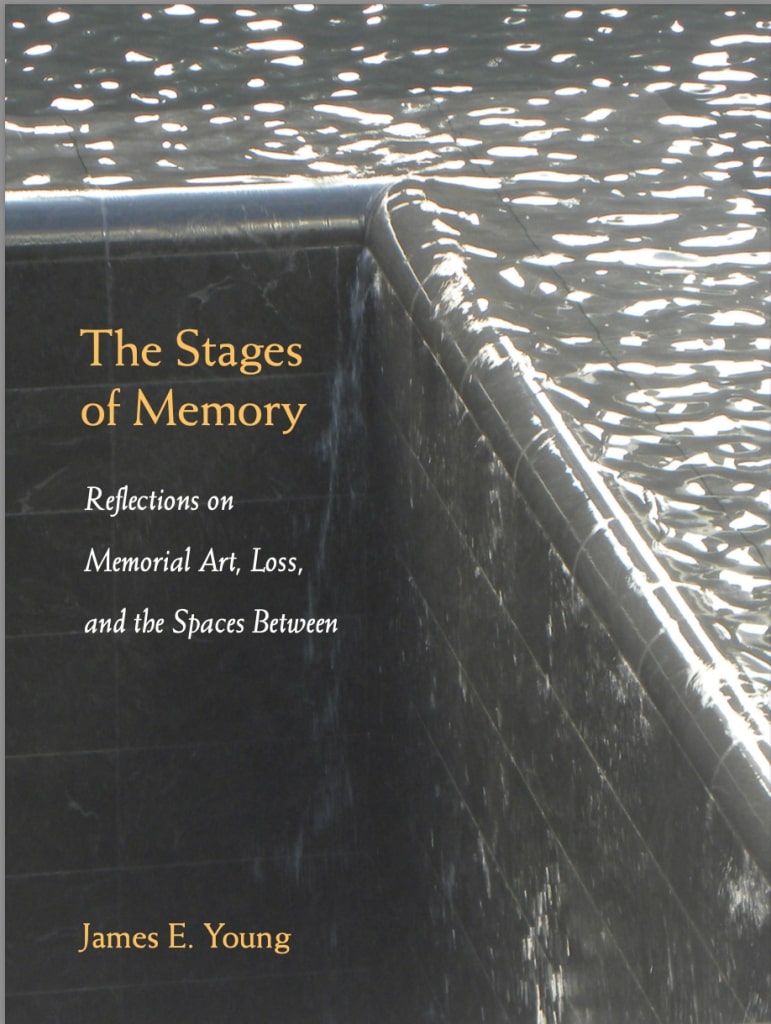

Young, a professor emeritus of English as well as Judaic and near eastern studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, recently spoke at the University of Rhode Island Center for Humanities Memorials and Commemorations in the United States series. His talk, entitled “The Stages of Memory: Reflections on Memorial Art, Loss, and the Spaces Between,” on Feb. 3 at 5 p.m.

According to Young, the architectural characteristics of memorials have changed throughout the past few decades.

What was once seen as tall and beautiful tokens of remembrance have shifted to catalyze feelings of contemplation and absence. Young discussed the importance of the stylistic decisions that were made when statues were created and how they reflect history.

According to him, Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans War Memorial was an inspiration for many memorial designs in Germany for future Holocaust memorials. Lin’s memorial, which is displayed in the Constitution Gardens in Washington D.C., is a black granite wall engraved with the names of service members who lost their lives in the Vietnam War.

“[Lin] opened a space in the landscape that she hoped would open a space within us,” Young said.

The memorial, which was opened to the public in 1982, influenced a vernacular that articulated loss and absence for visitors to contemplate and remember the Vietnam War.

This is evident in other memorials, such as Holocaust memorials, that Young discussed. Some artists, such as Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz who designed the Monument Against Fascism, have taken the concepts of contemplation, absence and the void from Lin’s monument and expanded upon it.

The monument, constructed in Harburg, Germany, remembers those who suffered under fascism throughout history. According to Young, the monument’s design was intended to change over time, unlike traditional monuments. Visitors to the memorial are asked to write their names on a 12-meter tall lead column as an oath against facisim. The column was gradually lowered into the ground from 1986 until 1993 when the pipe was no longer visible.

A sign next to the memorial reads “In the end, it is only we ourselves who can rise up against injustice.”

Young said the now empty space that the column used to tower in symbolizes the fact that a monument does not resolve national grievances and that it is the people’s responsibility to hold the world around us accountable for injustice.

He has been on the jury for deciding the designs of various memorials including the National 9/11 Memorial in New York City. The final design included two recessed voids where the twin towers of the World Trade Center once stood. Surrounding the two fixtures are groves of white swamp oaks.

“The taller these trees grow, of course, the deeper these voids will become,” Young said.

According to him, the use of voids and absent spaces creates a feeling of emptiness.

When the September 11 memorial design was announced in January of 2004, the press questioned the originality of the design.

“As I began to formulate an answer, I realized that the reporter did have a point,” Young said.

As he traced this arc of memorial vernacular, the themes of negative forms, absences and voids were constant. Young said that the memorial architecture reminds us that in order to remember life, we must contemplate loss.