Former Black Gold editor-in-chief reflects on campus experience

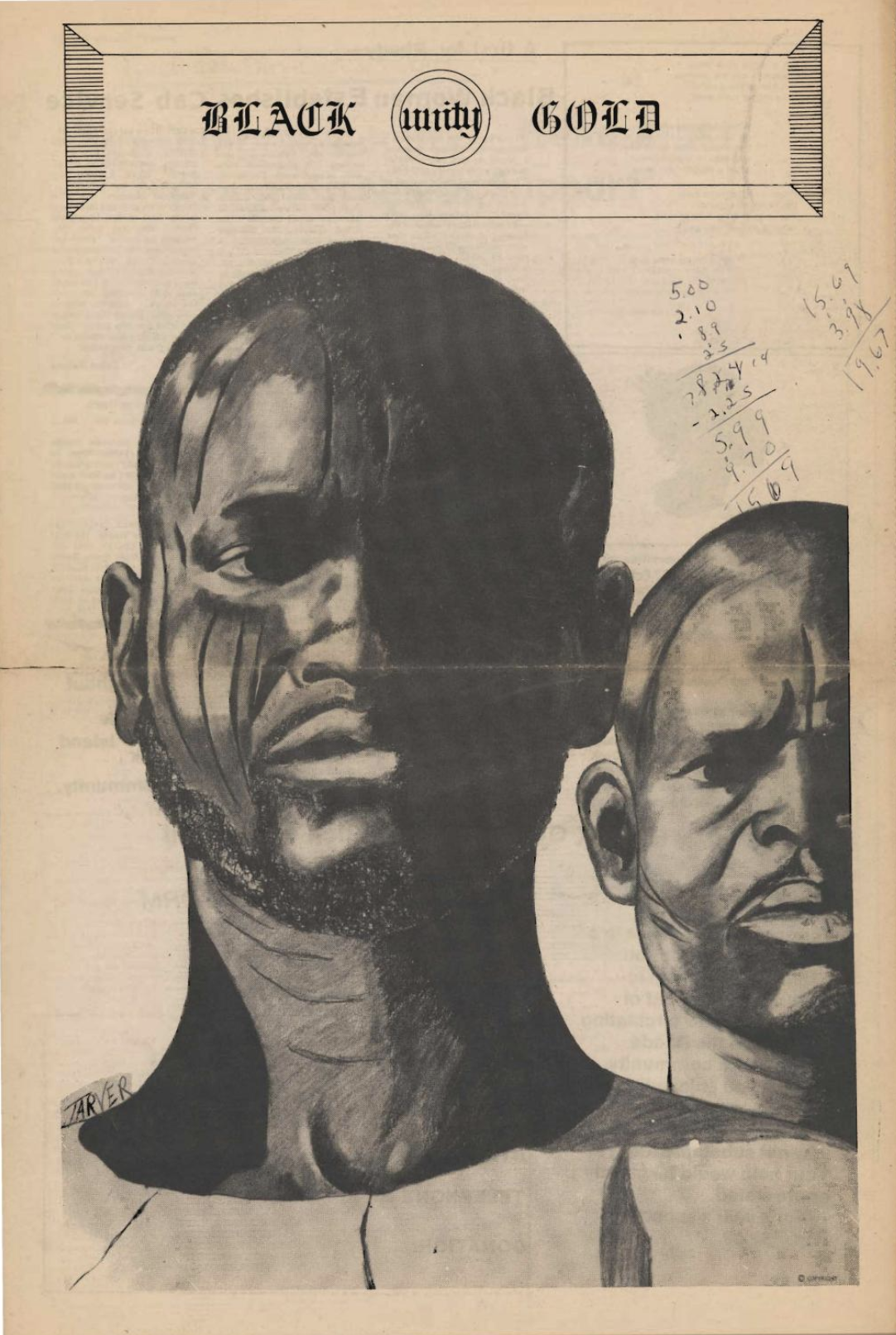

Page from the Black Gold paper 50 years ago. PHOTO CREDIT: URI Library Archives

Although the University of Rhode Island is currently only home to one newspaper, the Black Gold is a student newspaper that used to run alongside The Good Five Cent Cigar.

Valerie J. Southern ’75, M.C.P. ’80 is the president of VJS-Transportation Consultant, LLC, and the former editor-in-chief of Black Gold. Southern said when she was a student, Black students were concerned that the University wasn’t giving them the full recognition that every student deserved, and this thinking prompted discussions about starting a Black newspaper in 1972.

“It wasn’t any one student or one statement,” Southern said. “We just said, why don’t we have a newspaper? Why don’t we use the resources of the Black Student Union and publish our own? At the time we felt invisible and knew we would greatly appreciate seeing our voices and our points of view and reading articles of interest to us. So I became editor because my major was journalism, and I was very involved in Uhuru Sasa at the time.”

Abu Bakr, ‘73, former Chief Diversity Officer for the Center for Nonviolence & Peace Studies was also a student at the time of the Black Gold’s production. He said that the Black Gold made the University more welcoming to minority students.

“There were very few students of color, very few faculty, staff or administrators,” Bakr said. “The campus was not friendly or welcoming to students of color, but she [Southern] covered topics not covered by The Good Five Cent Cigar and it was highly regarded and widely read by students of color.”

Southern said that having a newspaper specifically for the Black college community was important because of the racism and absence of diversity on campus at the time.

“We felt this was better than trying to blend in with The Good Five Cent Cigar and its editorial policies that might not support our perspectives and beliefs,” Southern said. “We felt the funds from the student body should not be narrowly distributed to one newspaper or group of students, but it should be broadened.”

Despite being separate from the Cigar, Southern said that they initially worked closely with the Black Gold because they were able to share their resources.

“[The Cigar] had the resources to put together a newspaper; the hardware and software,” Southern said. “Some of the editorial team at The Five Cent Cigar said, ‘we’ll help you assemble your newspaper, use our resources,’ which we did. And then we published the first edition.”

Southern also mentioned that support from the Cigar was not universal.

“I think the reaction was mixed with people that helped us at The Five Cent Cigar,” Southern said. “It wasn’t the entire staff. The feminists on staff in particular said, listen we’re part of the same energy so we’ll help, but it wasn’t like the entire Five Cent Cigar staff embraced us.”

The University as a whole had similarly mixed reactions about the Black Gold.

“It wasn’t hostile, but it also wasn’t a friendly response,” Southern said. “The more traditional folks, I think they just felt challenged and confused and wished it would just go away, wished we would go away.”

With the Black community at URI, however, the newspaper was well received.

“As it turned out, the concept of the Black Gold was met with great enthusiasm,” Southern said. “And it was in line with other activities that we were undertaking, such as an annual cultural diversity program that we initiated. It brought talent from the American Black community to the University. So at the same time that we initiated Black Gold, we were engaged in sponsoring campus-wide cultural awareness events which we did every year until I graduated. The program dedicated an entire week to bringing in artists, filmmakers, historians, intellectuals and prominent political figures from the national black community to URI. This had never been done before.”

Bakr said that the emergence of the Black Gold came at a time at URI when social change was abundant.

“The Afro-American Society staged a first mass protest and occupation of the Administration Building,” Bakr said. “They aired grievances and demands that had a major impact in terms of recruitment of more students and faculty of color. Activities of the students and later staff led to the creation of the Office of Multicultural Student Affairs and although it took decades to accomplish, the creation of a Chief Diversity Officer.”

He said that student activism on campus encouraged the University to offer more diverse academic, cultural and artistic offerings to the URI community.

In terms of running the paper, Southern said that there were about four to six consistent members of the editorial team that worked to get the publication out.

“They did the interviews, writing, editing, design and got it to the printer on time,” Southern said. “We felt it was a good, solid piece of journalism. And it was a joy. It was so much fun and we were so proud. Every time a publication came out we were just over the moon.”

Southern said that the paper was timely, both in terms of the University’s and the country’s political and social climates.

“Nationally, folks, white and Black, were protesting the war, racial inequality and demanding women’s rights,” Southern said. “Our voices merged nicely with the feeling of the country, the feeling in the state and the feeling on campus.”

The contents of the paper were different from the Cigar because they were focused on the Black student voice and because of its volume of poetry and art in addition to news articles.

“Members of the community contributed stunning poetry and artwork and photography to Black Gold,” Southern said. “The talent that these black students had! The first edition was really a statement. It said, we’re here, this is our first edition and it felt necessary to voice who we were and to communicate our anxiety as well as our pride. It represented the majesty of being a person of color and we felt that this was just as important as any other aspect of University life.”

Southern said that the entire paper’s staff agreed that the paper should be available to more than just the URI community.

“We agreed that we would distribute it not only on campus but to the Black community in South County, in Newport, and to the community agencies in the Providence area,” Southern said. “We weren’t elitists and questioned why we should keep the paper to ourselves. To our surprise, the communities were just so pleased whenever we dropped off an issue. They looked forward to reading it and commenting on the imagery and narratives. This propelled us to publish it as much as we could.”

The Black Gold went on to publish at least 10 editions but published its final paper on Dec. 19, 1973.

“There was a hope that it [Black Gold] would continue with Uhuru Sasa, the campus black student union,” Southern said. “And that when we graduated the newspaper would become a tradition as opposed to just something that we did in our time on campus. I don’t think it stopped because there was no interest, I just think the next generation of students were involved in other things. I’m not sure if there were any black journalism students in the next generation.”

Although the Black Gold did not continue past Southern’s tenure at URI, she said that the paper has lasting impacts.

“It still surprises me, 50 years later, that people are calling and asking about Black Gold,” Southern said. “At the time, we were kids so we didn’t have a view into the future. We were just making a statement; and understanding who we were as black students. Newspapers have a way of impacting history because they tell you your story. I believe Black Gold opened the door for the black student body to be finally heard and seen, and forever changed the University along the way.”