The $205k award will help reduce contamination, mislabeling

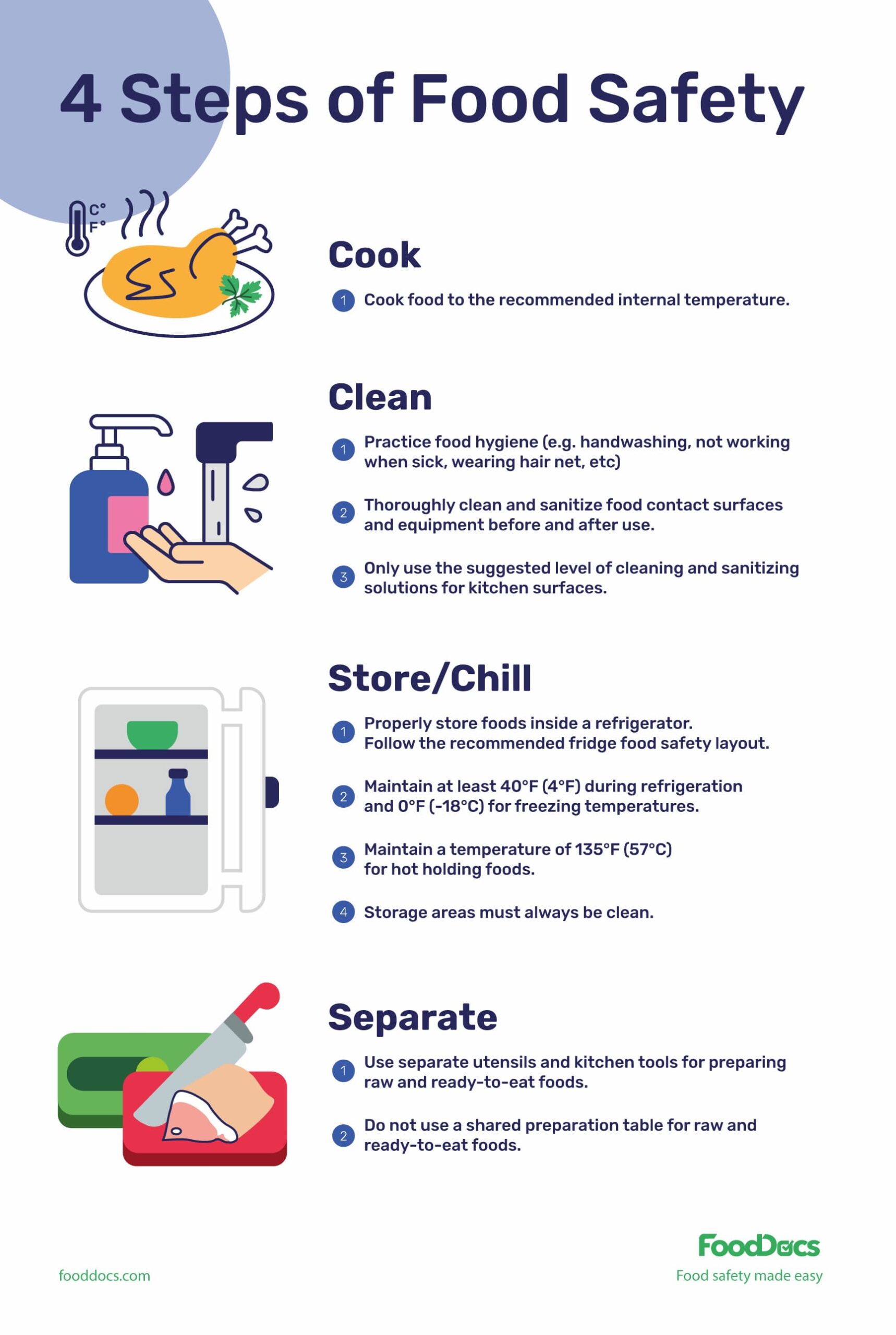

Four steps to food safety. PHOTO CREDIT: fooddocs.com

Nicole Richard, a research associate and food safety specialist at the University of Rhode Island, received a $205,000 federal grant that will equip compilable Rhode Island food manufacturers with specialized education and training in order to strengthen the state’s food safety system.

The project, funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) through 2024, aims to expand knowledge and awareness through food safety regulation practices with the goal of reducing issues such as contamination and mislabeling that occur during production.

In production, food safety preventive control measures must be both implemented and verified by employees, and a failure to do so could result in recalled food, according to the Project Narrative for Richard’s grant.

By making food manufacturers more aware of their role in producing safe food and teaching them in detail how to comply with safety regulations, Richard hopes to largely prevent instances of foodborne diseases.

This project is within URI’s Cooperative Extension Food Safety Education Program, and will include working with Polaris Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP), a non-profit organization that provides improvement programs for Rhode Island manufacturers.

Because the project is community-based, it relies on the assessment of compilable Rhode Island food manufacturers in order to determine the specific education and outreach needs of each manufacturer, according to the project narrative. These assessments will be in the form of paper, online and over-the-phone surveys, according to Richard.

“Most [manufacturers] are just trying to do the right thing, but they don’t know what it is,” Richard said. “We’re hoping that we can let them know we are here and focusing on them.”

The training of these manufacturers is a requirement of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) Preventative Controls for Human Food (PCHF) regulation, according to the project narrative. Yet, there is no assessment of the status of food companies regarding compliance with this FSMA PCHF rule. Richard’s project aims to correct this.

The opportunities for error in production that result in recalled food can range from an issue in the validating process, like checking the temperature of meat, to incorrect sanitation methods, according to Richard.

Employees could be cleaning equipment incorrectly or inadequately, which risks contamination. Manufacturers could also rely on their suppliers to control a hazard, resulting in miscommunication and possible dangers. Richard explained that manufacturers must show documentation of these correct sanitation and control procedures.

Recalled food is separated into three classes, distinguished by the product’s health consequences, according to Richard. The first class of food denotes a reasonable probability of serious health consequences, such as death or serious injury. The most common example of this is undeclared allergens on food labels, which account for a third of recalls.

When a food gets recalled, Richard explained that in addition to removing the food from the market, manufacturers must document and destroy all products impacted.

“Pour bleach on it, open all the bags… destroy it so you can’t get it back,” Richard said.

When URI’s Dining Halls have instances of recalled food, they lose money and experience a delay in time and service, according to Pierre St-Germain, director of Dining Services.

Dining Services has experienced pandemic-related production issues up until this past year, which requires similar efforts of food removal and replacement. St-Germain explained that these manufacturing errors happened before the food reached the University.

Although recalled food does not happen very often to URI Dining Services, they still have a critical control plan for if such instances were to occur, according to St-Germain.

This safety plan includes removing the recalled food, marking them as temporarily unavailable on the website for Dining Services and then looking at what is in stock to make substitutions, according to St-Germain. Dining Services uses specific brands and foods in order to comply with allergen requirements, so instances where they must make menu replacements impact URI at a student level.

“What we’re trying to accomplish is sort of twofold,” St-Germain said. “We’re trying to remedy everything and at the same time make sure to comfort everybody so that they feel safe at the dining hall.”

Instances of recalled food would impact URI greater if it were a smaller school, according to St-Germain. This is because, as a larger university, URI has more fall-back food items and opportunities for remedy and comfort within the community.

Richard’s project is only dealing with operations that have food safety plans, which doesn’t include retail operations such as grocery stores and restaurants, which are under different regulations.

By implementing specialized training and education programs for food manufacturers in the state, Richard’s project hopes to start to reduce instances of recalled food related to production. Once these businesses are equipped to comply with food safety regulations, they will be more likely to succeed in the marketplace.